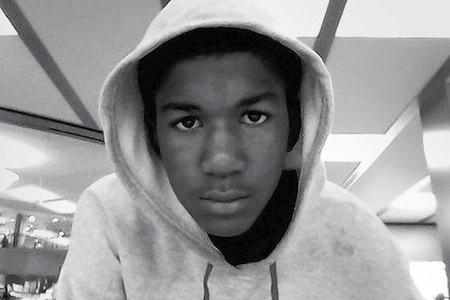

On the second anniversary of Trayvon Martin’s death, Khadijah Costley White meditates on his final moments and wonders if he knew how much he was loved.

I had managed to avoid listening to the 911 calls recording Trayvon Martin’s death until his mother’s testimony at his killer’s trial. I can still remember Sybrina Fulton sitting, stone faced, shedding tears as the audio of her son’s final moments echoed through the courtroom. I remember thinking that something was deeply wrong with a country that forces a mother to listen to her son die a brutal death as she stares at the man who murdered him. It’s a scene I’ve tried to forget.

But today, the second anniversary of Trayvon’s passing, I can’t help but meditate on his final moments. He was afraid that night, walking through the rain and worried about the stranger following him in a car. He was so close to home. He probably thought he’d make it, that someone would hear the commotion outside and come help. That maybe he’d get to finish the game he had been watching before he ran to the store for snacks.

I wonder when he realized that the stranger stalking him had a gun—did he see it and fight for his life? Or did he only realize that he would die when he felt the bullet tear through his young body? According to the city coroner, Trayvon stayed alive for several minutes after he was shot, laying face down in the wet grass. On the recording you can hear him begging for help. “You got me,” he told his killer as he was held down, his heart still pumping, filling his chest with blood. The doctors said he was in so much pain. Was he cold? Scared? Did he cry for his mom in those final moments?

With everything I am, I wish someone had held that child when he died. I wish someone else had been close by, that he hadn’t passed from this life to the next in the arms of his killer.

I wish he had no killer at all.

*****

My grandmother rarely finishes a conversation without saying how glad she is that she had a family. She says she prayed for us and God heard her. It’s a common refrain of hers and, as a child, I used to dismiss it as a familiar, soothing tune.

But as I get older, I realize that Nana’s commentary probably precedes both of us. How many black women in American history have wept and despaired after their children were taken from them? How many mothers went desperately looking for all their missing babies after slavery was finally over? For black folks, love and life have always been tenuous, always subject to the whims of white folks who never seemed able to see all that we were.

Our experiences and dreams have always been more faith than reality. We learned to love what life we had because it was always precious. And family was freedom—the joy of bearing a child and getting the chance to see who he resembled, to find out whether she laughed like you or had your father’s eyes. Family meant freedom, and freedom meant love.

So now, when my grandmother says she always prayed for a family, I think about love and freedom. I bask in her joy.

My brother, her second grandson, will turn 16 this year. He’s a small kid, skinny and scrappy, and knows how to play me for whatever he wants. He’s a boy and, as it often seems in the black community, this makes him special. When I was young, I always resented the delicate way black men and boys seemed to be treated, the ways their mothers and wives seemed to dote on them as if they were trying to make up for some deep wrong. Now I see that the irreparable betrayal done to them was being born in this country, in a society bent on containing or killing their kind. The black women I grew up with fawned on male children because they knew—despite jail cells and early deaths, police brutality and bad schools—that love was freedom.

As my brother fast approaches the age of Trayvon when he lay bleeding to death on a stranger’s yard, sometimes I see my brother’s face instead of his, and I can’t breathe for a while. I’ve thought, too often, that I would never survive if I lost him like that. That there would be too many pieces to put back together.

But then, I remember that I’m the descendant of the folks who survived. The ones who somehow resisted the urge to throw themselves to sharks as they crossed the Middle Passage. I’m the child of those who lived through slavery, smallpox, rape, prison leasing, sharecropping, and lynchings.

Trayvon was, too.

And that makes me think, that even as he lay in that grass, Trayvon knew he was. No one saved him that night, but caring hands had rescued him, held him, rubbed his back and kissed his cheeks many, many times before. And I think he remembered.

He was free. He was loved.

So, as we continue to be reminded that the murder of a black boy may never be valued in a legal system that once deemed black folks as less than human, as we collectively grieve for those we lost and those we have yet to lose, this one thought comforts me.

He was free. He was loved.

Khadijah Costley White is a faculty member in the Department of Journalism and Media Studies at Rutgers University in New Brunswick. Find her on Twitter here.

Related Links: