Violence is not something we can escape simply by creating more gender-equal societies.

From Germaine Greer to the Guerrilla Girls to Lena Dunham, feminism has long attracted women who like to shock. No surprise then that Camille Paglia—the academic who last week exploded the feminist blogosphere with a TIME article arguing that rape culture was overblown and girls should be more concerned about evil psychopaths than drunk frat boys—once admitted that her “method is a form of sensationalism.”

Paglia calls herself a “notorious Amazon feminist” but nevertheless once wrote that “If civilization had been left in female hands, we would still be living in grass huts.” But last week, she infuriated activists across the U.S. with a piece the Daily Mail summarized with the following gleeful headline: “Feminist: Colleges should spend less time on sexual political correctness and more time teaching women about the real threat of stranger rape.”

In Paglia’s own words:

Wildly overblown claims about an epidemic of sexual assaults on American campuses are obscuring the true danger to young women, too often distracted by cellphones or iPods in public places: the ancient sex crime of abduction and murder…The sexual stalker, who is often an alienated loser consumed with his own failures, is motivated by an atavistic hunting reflex….

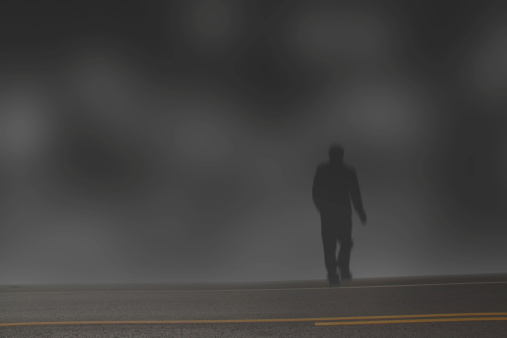

Young women do not see the animal eyes glowing at them in the dark. They assume that bared flesh and sexy clothes are just a fashion statement containing no messages that might be misread and twisted by a psychotic. They do not understand the fragility of civilization and the constant nearness of savage nature.

The argument has gained Paglia, a lesbian who says she has “personally disobeyed every single item of the gender code,” some very strange bedfellows. “There are few intellectual liberals whose intentions and arguments align with those of constitutional conservatives and libertarians more closely than Camille Paglia,” gushed the mag Personal Liberty. “Camille Paglia Gloriously Smacks Down Feminists’ Unserious Campus Rape Drivel,” said the conservative digital Daily Caller, and Salon’s Katie McDonough reports she first received the link to Paglia’s piece from an anti-feminist man who described Paglia as “someone who has a clue.”

For my part, Paglia’s argument proved interesting because I’ve recently been accused of utopian feminist naivety myself. More precisely, a week ago I found myself in a tense discussion with a fellow expat, a 30-something American who argued that he could heedlessly sleep with 14-year-old Colombian girls because Biology. The debate ended when he snarled that I am “such a white woman”—and given how much I’ve written about feminism’s problems with class and racial privilege, I thought I should give his accusation some serious thought. Do I naively believe, as Paglia charges, that feminism can “fundamentally alter all men,” with their “atavistic hunting reflexes” and “savage nature”?

Well, it’s difficult to assess one’s own naivety, for obvious reasons, but I do know that Paglia’s—and my expat friend’s—view of male nature looks an awful lot like misandry, pure and simple. Along with McDonough at Salon, I’m perplexed by the glee from MRAs and other anti-feminists at this idea of a built-in male propensity to immorality. How is it that the very people who like to fling charges that feminists are “man-haters” take the greatest ideological pleasure in a view of male nature as singularly corruptible? I’ve examined before how this line of argument is most often propounded to excuse a lazy shirking of moral accountability from people with poor self-control.

Nevertheless, even while insisting that #NotAllMen carry around the potential to morph into violent psychopaths, we’re still left with the task of understanding and deciding how to respond to the existence of the ones who do. While thinkers as important as Harvard’s Steven Pinker have made a convincing case that we are living in the most peaceful period in human history, we are still confronted daily with shocking headlines of isolated, unthinkable violence that feed into our collective anxiety over the evil side of human nature.

From ISIS’s recent murder of a women’s rights lawyer, to the murder of two British holidaymakers in a tourist hotspot in Thailand, to the disappearance of University of Virginia student Hannah Graham which prompted Paglia to write her TIME piece—perhaps the most paralyzing thing about the logic of the current violence is its lack of logic.

In fact, strange and outrageous as some of Paglia’s conclusions are, her morbid fascination with human evil, seen not just in her TIME article but as far back as her first book Sexual Personae, is not exactly an aberration in modern feminism. For instance, M.I.A., whose fuck-you attitude in singles like “Bad Girls” have made her a personal feminist hero of mine, forced her fans to confront their own bubble-gum-feminist discomfort at reckoning with senseless violence in her gruesome music video “Born Free” (although her concern here is with political rather than strictly gendered violence). [Trigger warning: Graphic portrayals of extreme violence.]

But it is one thing to explore how human evil breaks forth into nonsensical violence, and quite another to argue that society should intentionally circumscribe itself out of frightened deference to the power of “evil” men. This is effectively what Paglia is suggesting when she implies that young women should imagine the potential responses of psychopaths when choosing what to wear every morning.

We can see a feminist writer who started with similar concerns as Paglia but ended in a very different place in Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the novelist made famous for having inspired Beyoncé’s feminist awakening. The book narrates the story of Ugwu, a good-hearted 13-year-old forced to become a child soldier in the Biafran war, who eventually becomes a gang-rapist. Sounds horrific, and it is, but ultimately Adichie finds a way to bring the story back round to hope and redemption. If she were Camille Paglia, however, she would have concluded that Ugwu, as a male, should simply be written off as a person at the mercy of his own “atavistic hunting reflex,” and that women should structure their lives around a generalized fear of and precautions against such male moral corruptibility.

But for all my objections to her thesis, I still think Paglia raises important questions about how “empowered” women should engage with the threat of violence. As a feminist activist living in a country plagued for the past 50 years by civil conflict, I often worry that it is indeed naive to assume we can eliminate gendered violence in places still riddled with insecurity overall.

Regardless of how “empowered” we have become, to live in the world as a woman and expect it to be safe for us could be, well, dangerous. Violence is not something we can escape simply by creating more gender-equal societies, and simply believing that we “deserve” safety (although we do) is not in itself enough to keep us safe. Feminists must go out into the world and fight violence wherever we find it, and do our best to keep ourselves safe in the meantime.

But despite Paglia’s warnings, no one is helped when women nurse an inordinate terror at the would-be sociopath in the bushes. Refusing to be crippled and fenced in by our own fears might well kill us. But in 100% of cases, life will do that anyway.

Samantha Eyler is a freelance American writer, editor, and translator based in Medellín, Colombia. She has written about politics, immigration, Latin America, and social justice for publications such as NACLA and the New Statesman. You can follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Related Links: