There’s only one problem with paradise: it reminds you how unattainable it is.

The excitement builds for weeks, with the kids coming in to our room each morning to ask, “Are we going to see Grammie and Granddad today?” Finally, we get up in the middle of the night, load the mini-van, curb-check the car seats, and pass through security to fly from Cleveland to San Francisco.

When we arrive in Carmel after a day of traveling, we drag our bags inside the house and hug my wife Katherine’s parents, her three siblings and their spouses. Then we sit at the dining room table drinking Lagunitas IPA as our three kids run around the house, so happy to see their cousins again. We’re with our tribe. We’ve arrived.

Every day of our vacation is gloriously, beautifully the same: the kids wake up, smell the sea salt in the air and ask to go down to the beach. They take off their shoes and play in the sand as soon as we get there, and we spend half an hour climbing on the rocks and wading in the tide pools. “Can we put on our swimsuits?” they ask. We explain that the water in Northern California is too cold for swimming without a wetsuit, and they run and splash in the waves anyway, while the locals stare.

All week long, we play at Dennis the Menace Park in Monterey, build sand castles and watch the surfers in Santa Cruz, and go on boat rides in the Elkhorn Slough, where harbor seals frolic in the water, swimming right up to our boats like they’re shills for the tourism bureau.

There’s only one problem with paradise: it reminds you how unattainable it is. When I’m at the Safeway picking up beer, I realize you could fit half of our neighborhood grocery store back home in the wine section. I stand in line with older white retirees in yoga pants who are buying $4 organic tomatoes and kale chips. Everyone here is a member of the superrich elite.

Katherine and I are solidly middle-class, yet when we visit her family in Carmel, California, we don’t feel that way.

The widening income gap is affecting families. From 2009 through 2012, income for the wealthiest one percent of households surged 31 percent, after adjusting for inflation, according to research by economist Emmanuel Saez of the University of California at Berkeley. For the rest of us, income rose just 0.4 percent.

Hanging around the Google set makes me feel like we’re Rust Belt bumpkins. In the evening, after we grill salmon and watch the sunset, the parents get a rare chance to eat dinner with adults while the kids sack out on the living room rug and watch a movie. My in-laws talk about their trips to France and Germany, while we talk about our Groupon to the local water park.

The thing is, we’re hardly slackers: Katherine and I both work, we own our house, and we have money to pay for extras like piano lessons. Yet we stretch to be able to afford the annual trip to California, charging the tickets to our credit card or asking Katherine’s parents for help. With the U.S. Department of Agriculture saying the cost of raising a kid from birth to adulthood is now at $250,000 and projected to double by the time our kids reach teenage years, raising kids is increasingly unaffordable.

The income differences in my wife’s family, who are kind people who never make us feel unwelcome, can lead to some uncomfortable moments. When we visit a country club, Emily, who is 6, asks, “Mommy, are we members of a club?” Katherine and I exchange looks and explain that we use our family members’ clubs while we’re with them. Katherine’s parents split their retirement between Carmel and Kansas City, and that also leads to some confusion because we visit them in both places. After touching down at San Francisco International Airport, Nathan yells “We’re in Kansas City!” sending peals of laughter through coach.

My parents lived in San Francisco in the 60s when there were more Volkswagens than Priuses. Even before I set foot here, their romantic stories of living in Chinatown filled my dreams. Yet when I’m thinking rationally, I ask myself: Why would I want to live here? You can’t swim in the ocean unless you’re my kids, who think 50 degrees is warm. The traffic is awful and you need to make $200,000 per year to buy a house. Getting on the waiting list for daycare when your child is in utero is “normal.”

Psychologists call my sense of inadequacy “relative deprivation.” The wider the income gap becomes, the more middle-class people like us experience the sense that we don’t have enough, even if by objective measures we’re doing fine. And when I look around, I know this is true. My high school buddy in the East Bay, a self-employed contractor, has a house that’s half the size of ours and he worries about paying for daycare bills for his two kids. Neither of us are saving as much as we should for retirement, but I console myself that at least the beers at my neighborhood bar are two bucks cheaper.

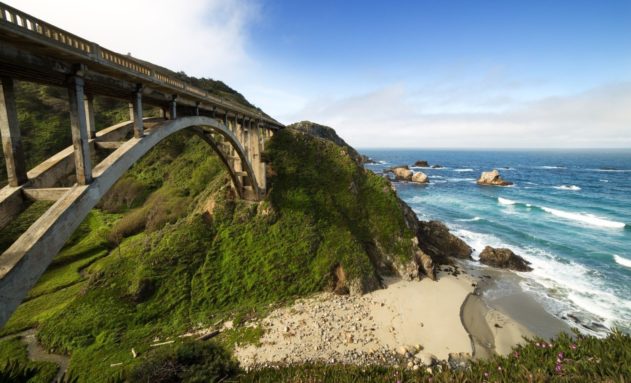

Yet beyond Carmel’s cute restaurants and wallet-draining tasting rooms, the old, wild California popularized by an earlier generation is still within reach. One morning, we stop in at the Big Sur Bakery after a hike at Andrew Molera State Park to pick up an almond croissant and chocolate chip cookies to go. Here in this coastal enclave, the old hippie California seems to have survived like some rare species of endangered fern.

As the week goes on, I slip deeper into vacation mode, noticing the succulent wildflowers along the beachfront path, the sun burning away the morning fog. With the help of built-in babysitters, Katherine and I get away once or twice for a date night where we sip wine and talk about the kids. Finally, we pack our things, our arms and legs sunburned, sand in our shoes, and board the plane home.

When we step out of baggage claim in Cleveland six hours later, cold air slaps us in our faces. We hop on I-71 to Cleveland, then get off at West 65th Street and drive past the Victory Lap Café, Scrap Mart and a discount department store called Roses that’s in an old K-Mart. We reach our gentrifying urban neighborhood, where our renovated Victorian house is a 10-minute walk from swimmable Lake Erie and we share a nanny with some of our neighbors. As we schlep our bags into the house, I push past the illusion that it’s small and old and begin putting things away.

Lee Chilcote’s work has also been published in Vanity Fair, Next City, Planning, Belt, AFP and other places. His poetry chapbook, The Shape of Home, was published in 2017 by Finishing Line Press, and he’s cofounder and executive director of Literary Cleveland.

Other Links: