What I do know—some days the only thing I know—is that I let her down. I probably couldn’t have saved her life, but I could have saved our friendship.

I opened my last wedding present three years ago, the day after my best friend died.

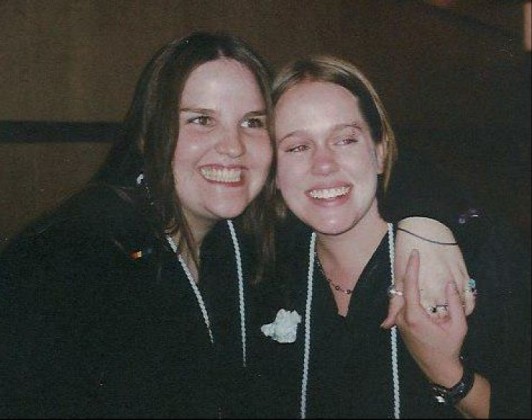

It had been almost five months since my wedding, which was also the last day I saw Heather alive. She was my maid of honor, my other half since seventh grade, the person I loved more than just about anyone in the world. We spoke our own language of inside jokes and code words. Our synchronized dances were never choreographed—they just sprang into existence. We had matching tattoos.

And yet, the year she died, we were drifting apart, struggling to reconnect but not quite making it.

The day of my wedding, Heather was late—so late she almost wasn’t in any of the photos. She had locked her keys in her car, something she did frequently. Her chronic absentmindedness dated back to the beginning of our friendship. She would show up to gatherings late or not at all. She came ridiculously close to not graduating from high school on time because she kept forgetting to turn in a huge assignment. I vacillated between finding this endearing and infuriating.

On the day of my wedding, I was fuming. Just as I was getting ready to say “fuck it” and start the photos without her, Heather showed up, flustered and apologetic and having left her present at home. Maybe it was unreasonable, but I was hurt that she couldn’t focus enough to be on time, just this once.

At that point, my relationship with Heather had become … not distant, but slightly strained. I was caught up in other things: getting married, finishing grad school, trying to find a job, and sinking slowly into depression when I couldn’t. Heather was busy caring for her ill husband and was so exhausted she was fired for falling asleep at work. (I later realized this might have been a symptom of the undiagnosed heart condition that killed her at the absurdly young age of 25.) Meanwhile, she was fighting with another friend of ours, and I was growing impatient with hearing both of them talk about it. I finally told Heather, “I’m tired of you only calling me when you have something to complain about.”

She called less after that. Even if I hadn’t meant to say “I don’t want to hear about your problems,” that was what she heard.

What I would have said, were I being honest, is “I don’t want to hear about your husband.” I couldn’t stand her husband. I thought he was selfish, manipulative, and totally unworthy of Heather’s devotion.

Heather was fiercely loyal even when she shouldn’t have been. She wouldn’t tolerate anyone speaking ill of her husband. When a good friend gently mentioned that she didn’t think Heather was getting as much out of her marriage as she was putting into it, it created a giant rift in their friendship. By the time Heather died, the two of them were hardly speaking.

After watching that happen, I knew there was no way to tell Heather that I hated her husband. If I did, it would only push her into an us-vs.-them worldview where I was on the side of “them.” Instead, I kept my mouth shut, making excuses not to show up for events if I knew he would be there. I called Heather on the phone instead of going to her apartment. I let weeks, then months, pass without seeing her face-to-face.

I thought our friendship was going through a rough patch. I assumed we would get through it. I even hoped, somewhere in the back of my mind, that one day she would reach a breaking point and leave her husband, and the vibrant, passionate, ambitious Heather of my youth would burst forth from her cocoon of exhaustion. In the meantime, I put a little distance between us, telling her not to lean on me without saying the words.

As I planned my wedding, Heather and I kept trying and failing to get on the same page. I was upset that she left my rehearsal dinner early; she was upset that I didn’t take her dress shopping with me. We both felt shunted aside, deprioritized. We both wanted more from the other than we were getting. She left my wedding early because her husband didn’t feel well. I’ve tried so many times to remember what I said as I hugged her goodbye that night, the last words I ever said to her face-to-face. I think—I hope—it was “I love you.”

Two days before she died, she texted me. I deleted the text, but I can still see it with perfect clarity: “Hey, lady! I am missing you. Phone date soon?” I texted her back the next day, suggesting we get together that weekend. I don’t know if she ever got my reply, if she checked her phone in the hours before she died or if she was just too tired. I know that on that night she lay down on the couch to watch “Law & Order” reruns and never got up again.

I wonder every day if there was something I could have done. Maybe if I’d seen her in those last few weeks, instead of just talking on the phone, I would have noticed something was wrong, convinced her to go to the doctor before it was too late and her heart gave out. Probably not, but of course I’ll never know.

What I do know—some days the only thing I know—is that I let her down. No matter how many times the people closest to me reassure me that it isn’t true, that she knew how deeply I loved her, I can’t convince myself that I’m off the hook. I probably couldn’t have saved her life, but I could have saved our friendship.

The day she died, we gathered at her mother’s house to hold each other and cry and drink and try to figure out what the world looked like without her. Heather’s mom pressed a box wrapped in shiny opalescent paper into my hands. “Your wedding present,” she said. “I don’t want to forget about it again.”

At home the next day, I sat on the floor and opened it, trying and failing not to rip the wrapping paper. Inside were the last gifts I’d ever receive from my best friend: pot holders, an apron, a glass pitcher, and a candy dish shaped like a seashell. I curled up in a ball and sobbed.

I have never tried harder to believe in the afterlife than I did after Heather died. I recited Hail Marys and Our Fathers like I hadn’t done since elementary school. I gritted my teeth and tried to conjure up an image of a higher power—anything, anyone, beyond the reach of mortality. If I could convince myself that some part of Heather’s essence still existed, then I could apologize. It was never in Heather’s nature to withhold anything from someone who needed it, and that includes forgiveness.

But I couldn’t ask, because I couldn’t make myself believe that I was talking to anyone but myself. And unlike Heather, I’m not built for forgiveness. Without a way to make things right between us, I’ve had no choice for the last three years but to live with them being wrong.

Every day, I go through my life surrounded by small reminders of Heather. I put the candy dish on a shelf with a picture of the two of us and her old C3PO Pez dispenser. I drink iced tea out of her pitcher. Sometimes these little vestiges of her feel like comfort, and other times they feel like penance. It hurts to remember all the things she gave me that I’ll never be able to thank her for, but the pain is better than not remembering at all.

Photo of Heather, left, and Lindsay at high school graduation in 2005.

Lindsay King-Miller is a queer writer who lives in Denver with her partner, an ever-growing collection of books, and a very spoiled cat. Her first book will be published by Plume in early 2016.

This originally appeared on Fusion. Republished here with permission.

Related Links: