This post originally appeared on the Women’s Media Center. Republished with permission.

The author, a nationally recognized authority on the choices women make as they age, analyzes a new study that tracks an unrealistic and stressful standard of perfection for men.

In 1963 Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique identified The Problem That Has No Name—a soul-destroying malaise and sense of uselessness that beset the woman who had bought into the “mystique” of perfect wife, homemaker, and mother. Because she wasn’t happy, she thought something was wrong with her. The second wave of the Women’s Movement gave a name to that problem and countless other experiences that women were afraid to discuss.

Everything changed in the seventies and eighties, and an unintended consequence of the revolution in women’s roles was a new mystique—Having It All. The woman who couldn’t juggle work and family, couldn’t cheerfully “bring home the bacon and fry it up in a pan”—as the Enjoli perfume ad proclaimed—felt once again that something was wrong with her. We struggled to ward off the guilt and break free of that mystique too.

Now, as gender roles adapt to new family values, comes a new mystique—“the male mystique,” so named by the prestigious Families and Work Institute in a recent study. It finds men increasingly stressed out by trying to achieve an unattainable standard of the perfect father, husband, and breadwinner. Just like Having It All, this mystique is an unintended consequence of a revolution in the way men and women relate to each other. Back in 2000, in my book Father Courage: What Happens When Men Put Family First I talked about men who desperately wanted to be more involved with their families and do more of their share at home but were constrained by the workplace culture and the prevailing image of how a Real Man prioritized his work and family. One told me that he was so afraid of getting caught leaving his office at 6:00 and being thought not committed to his work that he parked in a distant corner of the parking lot. Another told me that when he went to the playground with his baby daughter on a weekday, people assumed one of two things—that he was unemployed (a failure) or a sexual predator.

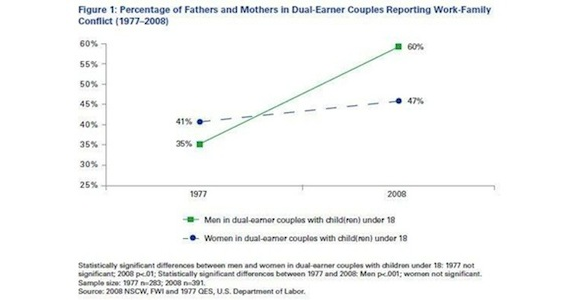

Since then a lot has changed. My neighborhood is full of fathers pushing strollers or wearing Snugglis or wiping a messy chin at all hours of the day and night. But the Families and Work Institute reports that they are paying a price. “The New Male Mystique” is stressing out the men who are trying to balance work and family—even more so than women, the study reports. They are finding that the new male version of Having It All is a model of masculinity that is just as oppressive as the Master of the Universe model was 20 years ago.

Is this bizarre turn of events just another example of the “be careful what you wish for” retribution for women? I don’t think so. For one thing, those men are still doing less of the household tasks and childcare than their wives, so in that department, we are still wishing. But I think the stress that now crushes men as well as women who are trying to maintain family life and a serious work life at the same time is due less to impossible role expectations than to the unchanged, inflexible, and inhospitable mystique of the workplace itself.

Over the decades in which almost everything else changed, the shape of our work life has barely shifted off the classic 9-to-5 time frame—or more likely, 9-to-6, 7 or 10—and the drive-to-the-top career trajectory. Sure, technology has made it possible to work from home, but for many that means working all night instead of all day; flextime, job-sharing, family leave and childcare policies have barely made a chink in the structure. They have not been backed up by realistic social services and tax codes or the kind of adjustments in the workplace culture that reflect management that is walking the walk.

Instead of supporting the more nurturing and equitable family model, the message from our day jobs remains: when it comes to balancing family and work, if you can’t manage on your own, it’s your comeuppance for wanting to Have It All. By definition “mystiques” reflect models that no one ever lived up to but everyone feels they ought to. Humanizing the model could reveal a collective, societal solution to the work-family “balancing act,” allowing what life cycle pioneer Erik Erikson called the “cornerstone of our humanness”—a healthy combination of work and love.

Suzanne Braun Levine writes about the opportunities, challenges, and adventures being experienced by women at midlife. Her forthcoming book “How We Love Now: Sex and the New Intimacy in Second Adulthood” continues the conversation she began with “Inventing the Rest of Our Lives: Women in Second Adulthood” and “50 Is the New 50: Ten Life Lessons for Women in Second Adulthood.” She was the first editor of Ms. Magazine and the only woman editor of the Columbia Journalism Review. With Mary Thom, she co-authored an oral history, “Bella Abzug: How One Tough Broad from the Bronx Fought Jim Crow and Joe McCarthy, Pissed Off Jimmy Carter, Battled for the Rights of Women and Workers, Rallied Against War and for the Planet, and Shook Up Politics Along the Way. Her blog, Women in Second Adulthood, is at www.suzannebraunlevine.com.