Sociologist and mob-mentality expert Elaine Replogle discusses why gang rape happens far too often.

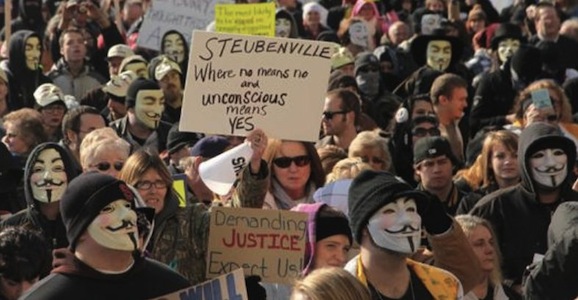

Football players at a party in Steubenville, Ohio. Gang rapes in India. Mob sexual violence in Egypt. Rapes of women—often by groups of men—in Syria. Or the Congo. Or Texas. Or in the military. Or…

There is something very understandable about gang violence (people are more likely to do something if they think they can get away with it, and large numbers, ironically, provide some statistical likelihood of not getting caught). Similarly, there is something very puzzling about it (why don’t bystanders intervene more often; how can people let themselves behave so atrociously just because they’re in a group?).

The answers to these questions are often found buried in textbooks or academic articles and do not, frankly, lend themselves to the most fascinating reading. Fortunately, I cannot claim to have been a victim of gang violence. And yet, like most of us, I’ve had experiences where somebody could have come to my aid (however minimal) and did not. Where it felt like a bystander should have done something and failed to do so.

Thinking about why people don’t intervene—especially when they can—is a place to start to unpack the psychology of gang rape.

For instance, in the summer of 1988, I was a junior at Earlham College and an exchange student in Valencia, Spain. I was 20 years old and had just, three months prior, experienced the tragic loss of my 14-year-old brother in a freak hiking accident. Newly bereaved and suddenly keenly aware of the gazillion ways you can die, I was paralyzingly risk-averse (even more so than usual—nobody would ever describe me as a thrill-seeker). But I was also starting to come out of that early period of dark gloom of new trauma, and had become friends with another 20-year-old studying in Spain, a Dutch woman named Saskia.

One evening, tired of studying and invigorated by warm temperatures, Saskia and I asked our host mother if she thought it was OK for the two of us to go out. Certainly, many of our friends (Spanish, American, and Dutch) had been going out regularly—drinking, clubbing, partying, being young. Saskia and I had stuck out, to our minds at least, as the weird young foreign women who did not.

Our host mother said it would be fine. We discussed where we’d be—in downtown Valencia, where on a hot summer night, there are always plenty of people—and we left at about dusk.

About a half hour later, we were walking across a pedestrian bridge, enjoying the atmosphere of so many people out and about when Saskia grabbed my arm. “Behind you,” she gasped. I looked behind to see a man, pants unzipped and with a huge erection, reaching toward me. He was within inches of actually being able to grab one of us.

Saskia and I grabbed each others’ hands and ran, screaming.

As we escaped, we heard laughter. Later, we would discuss this and realize that others had witnessed what was happening. Their response was laughter.

Not help. Not sympathy.

Laughter.

I had a hard time stopping screaming; a few blocks away, Saskia stopped and shook me, saying “You’re OK. He’s not behind us anymore.” I experienced a level of fear that night I have not (thankfully) had since.

When we got back to the apartment, our host mother helpfully told us that the near-attack happened because Saskia was blonde and I was American. (A near-constant topic of conversation with my Spanish male friends was about the supposed “easiness” of American women, and how I just didn’t fit that stereotype. Was I really American?)

Victim-blaming. Stereotyping. The fodder of sexual violence.

Over the years, I’ve thought quite a bit about that near attack. About how “lucky” we were. About the victim-blaming. And about the witnesses.

This wasn’t something that happened in a dark, deserted parking lot or stairwell with nobody around. This happened in front of many people—dozens, if not more. And the only response I was aware of from those people was laughter.

Was the “attack” only intended to scare? Was the man dared by friends to do what he did? Were those who were laughing known to him?

I don’t know the answers. I do know, from my professional life as a sociologist who has read a good deal on bystander behavior, that such behavior ranges from the noble (intervention) to the shameful (purposeful ignoring) to the misguided (failing to intervene because the situation is not correctly perceived). In their now famous 1969 article on bystander apathy, sociologists Latane and Darley argued that bystanders are most likely to intervene when they correctly interpret the situation and think that it is possible to intervene and feel competent to do so.

It’s not hard to imagine a bystander feeling nearly as overwhelmed by a gang or a mob as the victim herself, something that aids, psychologically, the perpetrators themselves.

Many sociologists, including Beth Quinn have argued that other men are often the intended audience of sexist gestures and comments and that harassment has much more to do with keeping women in their place than with sexual attraction. Logically, gang rape is explained more by men’s “need” to perform gender for other men than it is explained by any kind of “irresistible” sexual desire.

If a person in a large group thinks they can get away with a behavior, they are more likely to do it if it is a behavior that appeals to them and is, on some level, already condoned.

Sexual attacks—particularly of women—are, on some level, condoned by society. We’re told, sometimes explicitly, that women “ask for it” by being alone, wearing short skirts, dressing “sexy,” partying, drinking, having loose hair, wearing tight clothes, wearing impractical heels, hanging out with the “wrong” people. Wrong place, wrong time, bad choices.

The list goes on, of course.

Few people, if any at all, actually say in so many words that sexual attacks are acceptable. But when victim-blaming is pervasive (despite notable and well-publicized articles criticizing it) and when boys are taught (however subtly) that women’s bodies are for their pleasure, it’s not a stretch to think that some men, in groups, might think it’s OK to abuse women. They might not even think that carrying around a drunk sleeping woman by her ankles and wrists constitutes “abuse.” They might think (however stupidly) that if they don’t perform some sexual act on an incapacitated woman (whether by drugs or alcohol or force), they are lesser “men” than the other men in the group.

When you then consider how few men ever are convicted of rape, you realize that there’s a subtle message: It’s not that bad. If it were, wouldn’t we try harder to prosecute the perpetrators?

The psychology of gang rape is aided by numbers, by underlying aggression, anger, and misogyny, by what Gloria Steinem terms a “cult of masculinity” and by a culture that does too little to hold perpetrators accountable.

With that combination of factors, it’s not hard to understand why many men in a group would think a man with an erection behind two 20-year-old women was nothing more than terribly funny.

Elaine Replogle graduated from Earlham College in 1989, completed a Masters in Theological Studies at Harvard in 1994, and got her doctorate in sociology from Rutgers in 2005. She currently teaches Sociology of Mental Health, Sociology of Health and Medicine,and Social Inequality at the University of Oregon. Last year she published “Reference Groups, Mob Mentality, and Bystander Intervention: A Sociological Analysis of the Lara Logan Case” in the journal Sociological Forum. She is married with three children.

Related Links: