With so few women in powerful positions, we expect those who are to represent all of us, but that’s not fair, says Emily Heist Moss.

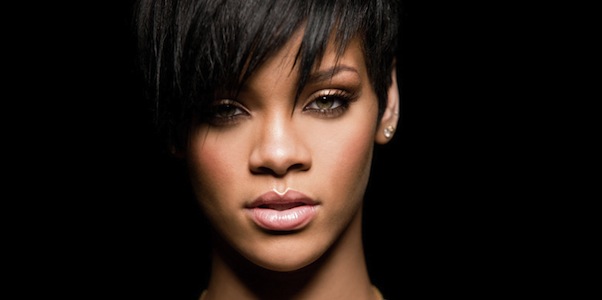

Here’s a thought I’ve had before: Rihanna is a terrible role model. If I were a parent, I would not want my daughters to look up to her.

Here’s a thought I’ve never had before, but I also think is true: Donald Trump is a terrible role model. So is Chris Brown. And Todd Akin. And Silvio Berlusconi. And Ben Roethlisberger. And Anthony Weiner. If I were a parent, I would not want my sons to look up to them either.

Why do I think about Rihanna’s status as a role model, or not, but don’t apply the same standards to male celebrities? I think it may be as simple as a numbers game. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of male celebrities and influencers eligible for “role model” status. The bad behavior of a few, though problematic, doesn’t seem to reflect more broadly on the gender as a whole. There is enough diversity in the pool that, as a parent, I’m confident I can find other people for my kid to look up to.

Not so for women, at least not yet. There are only so many women at the top. I realized recently that I’ve been expecting these few to represent the whole sisterhood instead of just representing themselves, and that’s clearly unfair.

*****

Against my instincts, which generally direct me to forsake what seems too trendy to be good, I’ve been reading Sheryl Sandberg’s bestseller, Lean In, a manifesto about women, work, ambition, sexism, and leadership. Before I even cracked the spine, I had put on my cynical glasses and donned my “This can’t be all it’s made out to be” hat. Everything I read about this book suggested Sandberg was delusionally privileged, lacking in empathy, and speaking to a very narrow (read: young, attractive, educated, wealthy, mostly white) segment of the population.

Those first two accusations proved to be completely false, but four chapters in and the last still holds. This is a book for a certain kind of woman and it is most definitely not a book for a certain other kind of woman. If your concern is working two jobs while earning a GED, this is not a book for you. If you have no desire to reach leadership roles and are content to put in a solid 40 and then peace out, this is not a book for you. If you’d rather be a stay at home parent, hitchhike from coast to coast or join the Peace Corps, this is not a book for you.

Critics seemed to think that these “oversights” are something for which Sandberg should be apologizing, and before I opened the book, I did too. Because she is at the top, I want her to speak for all women, and any inability to do so seemed like a missed opportunity.

If Donald Trump wrote a book about how to go from rich to richer, or how to have the worst hair ever, there would be no outcry about the poor people and baldies he was ignoring. We are able to acknowledge, when it comes to male influencers, that no advice is universal. In fact, most of it is very, very specific. But with women at the top, the fact that there are so very few of them means that we want them to represent all of us.

This is not unique to the ladies, but applies to any group whose slice of the “leadership” pie is disproportionately small. As Ta-Nehisi Coates has written regarding Obama’s presidency, those who make it to the top are held to the impossible standard of representing everyone who didn’t. Their failures are our failures, their successes are our successes, and their inability to meet all of “our” needs feels criminal because we have so few people to speak for us.

Straight, white, privileged men don’t need “role models” in the same way that the queer, non-white, underprivileged, or female populations do. Or rather, they need role models too, but there is no dearth to choose from, so no single man has to fit every bill, and address every issue. Some of you can look up to Einstein, and others to Jefferson. Some to Lincoln, and others to Shakespeare. Some to Tom Brady, others to Warren Buffett. Neither history nor the present has any shortage of successes who look like you. They are not all perfect, but they don’t have to be because they can paint a portrait of success that, collectively, is all-encompassing.

For everyone else, we have so few on the pedestal that we pin all of our hopes and dreams to them and then cross our fingers that they don’t screw up. And sometimes, they will screw up. Yahoo CEO and new mother Marissa Mayer got lambasted in the news last month when she canceled Yahoo’s work-from-home policy. She was criticized over and over again because “as a mother” she should understand the value of a flexible schedule and “as a woman” she should have more sympathy. Though I may disagree with her policy, or portions of it, her decision can’t be viewed through the “as a woman” lens. That’s not fair to her, and it’s not fair to the (hopefully) hundreds of female CEOs who will follow her. In a world where there are a myriad of female business leaders, the range of policy decisions they make will be just that, a range of policy decisions, rather than emblematic of What Women In Power Do.

*****

The flip side of this lack in eligible role models is that we are sometimes afraid to criticize the ones we have, lest we knock one of our few “winners” down too far. This is a mistake. As Anita Sarkeesian of Feminist Frequency puts it, “Remember that it’s both possible and even necessary to simultaneously enjoy media while being critical of its more problematic or pernicious aspects.” This is true of role models as well.

Let’s stop criticizing Rihanna, Sheryl Sandberg, Marissa Mayer, Beyonce, or the like for being “bad role models” or for being incapable of representing everything we want them to represent in one tidy package. Instead, let’s focus our discussion on where they have succeeded and where there are still gaps. Sheryl Sandberg’s book doesn’t address the realities of poor women struggling to meet the basic needs of their families, so let’s find some other books that do. The problem is not that our role models are imperfect, it’s that we have so few to choose from.

Emily Heist Moss is a New Englander in love with Chicago, where she works in a tech start-up. She blogs every day about gender, media, politics and sex at Rosie Says, and has written for Jezebel, The Frisky, The Huffington Post and The Good Men Project. Find her on Facebook and Twitter.

Related Links: