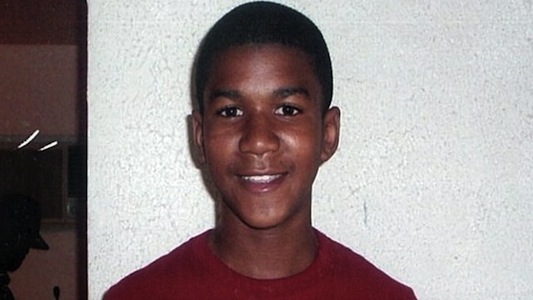

Role/Reboot Editor-in-Chief, Nicole Rodgers, discusses the privileges she enjoys as a white woman that a black teenage boy will never have.

Ever since Zimmerman was tried was acquitted, I’ve felt indignant, unsure how to express and process my anger and shame. Travyon’s story is not my story, so initially I chose to hang back, read everything I could get my hands on, and use my site to publish the words of others. But hearing calls for solidarity and shared outrage from white feminist allies has made me feel differently. I’m sharing what I experienced, as a white woman, the night Zimmerman was acquitted, and the often-invisible white privilege it exposed. This is not by any means the most important story: It is just mine. And that’s the only one I can tell.

*****

I was home Saturday night in D.C., glued to the TV, when Zimmerman was acquitted. Even before the words were uttered, I was anxious. I’d watched enough of the trial coverage and analysis to understand that Zimmerman might walk. When the verdict was read, I felt disappointment, anger, shame, and sadness, but not surprise.

On cable news, meanwhile, pundits displayed a nearly palpable excitement when forecasting the potential for riots. Without evidence that a single violent incident had occurred, they mused aloud about the aftermath of Rodney King, perpetuating the same racist belief Zimmerman’s defense team had successfully used the very same week to justify the murder of Trayvon Martin: that people of color are violent and unpredictable and pose a threat others must protect against.

I was conflicted. Any reaction that involved violence felt undesirable and would ultimately be used to reinforce the idea that people of color are dangerous, but the fear of nothing happening, and what that would signal, felt worse. This is the catch 22 for black citizens in America during all moments of grave injustice, I suppose: Get too angry and risk reinforcing others’ existing prejudices; respond too calmly and send a tacit signal that what has happened is OK.

In homes across the country, people were getting the message loud and clear: In America, an unarmed black teenager minding his own business can be found guilty of his own murder. An impromptu midnight march for Trayvon was promptly organized in D.C., and details spread like wildfire across social media. In no time at all, I could hear the noise of people congregating on U Street from my living room; I ran out into the 90-degree mugginess of the D.C. summer to join the growing crowd of marchers.

The crowd was young and from my vantage point, comprised of a slight majority of men and women of color. We all marched down U Street, up 18th Street through Adams Morgan, and then over into the heart of Columbia Heights. The marchers eventually stopped at an open pavilion in Columbia Heights, and soon after, a bullhorn was procured.

A young woman of color spoke first. She called for a night of reflection, and then asked people to come up to the front and say what they were feeling. “I’m sorry,” she said politely, referring to her call for speakers, “no white people tonight.” Some folks looked uncomfortable, as people often do whenever race is mentioned directly in public. But what she said felt right. It was right. It wasn’t my night, or that of any white allies in the crowd. I’d contributed my body to a peaceful protest as a show of solidarity with others reeling from a specific kind of injustice and heartache that I can only intellectualize and empathize with, but never fully understand. It shouldn’t be controversial in moments like this to ask white people to stand down and play a supporting role.

For the next 45 minutes, a handful of people of color spoke. What initially surprised me was that almost every person made a point to laud the solidarity apparently signaled by the mixed race crowd. Some referred to the crowd as a “rainbow,” and a few praised “all the races” in attendance. (At one point, even, in what appeared be a public gesture of inclusivity, a towering, skinny dreaded black man handed the bullhorn to a young scraggly white guy to speak, though as it turned out, he was either too fucked up or too overwhelmed to utter a word). One by one, numerous young men and women of color engaged in impassioned, heartfelt, sometimes rambling diatribes about structural racism (the speech of one young man who was a public school teacher in D.C. has stayed with me). Then most closed with proclamations about how we are all in this together.

But are we?

Like the now-famous tumblr said: I am not Trayvon Martin. I couldn’t put my finger on it exactly at the time, but while all the paeans to inclusiveness—to in-this-together-ness—were in some ways profoundly touching, they also made me incredibly sad. It was a generosity I felt undeserving of. A gift I hadn’t earned.

It wasn’t until I read Questlove’s piece in New York Magazine last night that I understood precisely what the strange nagging feeling was about. One paragraph summed it up well. Of his own experience, he wrote:

Seriously, imagine a life in which you think of other people’s safety and comfort first, before your own. You’re programmed and taught that from the gate. It’s like the opposite of entitlement.

As a white woman at that impromptu protest, I felt accommodated. Standing among a crowd made up of predominantly people of color, many appeared attuned to my comfort level. I was the beneficiary of generosity and the kind gestures of fellow protesters, who chatted with me and chanted with me throughout the night.

This is what privilege feels like.

On this particular night, knowing that a jury of mostly white women was at least partially responsible for the sadness around me, I felt a sense of shame. I know that I am no more responsible for the decisions other white women make than Trayvon was for the decisions of other black teenagers. But I also understand that I enjoy privileges as a white woman that a black teenage boy will never have. Nobody follows me around stores, or calls the cops when I’m in their neighborhood. I can join a midnight protest and feel welcomed. Nobody fears me when I pass by on the street walking home from a protest late at night. I don’t have to think very much about racism unless I want to. I am usually given the benefit of the doubt.

Does racial profiling have an opposite? Racial privilege? That’s what I felt.

Trayvon was killed by racial profiling; killed because some other black teens who looked like him had recently burglarized the same neighborhood he happened to be walking in. I was welcomed that night by a crowd of mostly people of color, despite the fact that earlier that evening, a jury that included five white women who may have looked a lot like me had let Zimmerman walk.

I guess I just want to say thank you to everyone I marched with that night. The only thing I can think of to do in this situation is to keep fighting, keep listening, tell my truth, and to acknowledge all the privileges I appreciate that others cannot access.

Nicole Rodgers is the Co-Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Role/Reboot.

Related Links: