Emily Shepard discusses the importance of letting kids be who they are—even when it goes against what society says they should be.

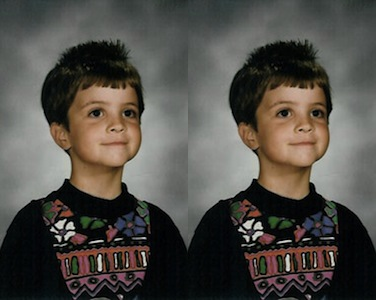

In first grade, I said I wanted to be a boy. I demanded short, spiked hair and my favorite shirt had a surfing T-Rex on it.

I am not a transgendered person.

At the time, people thought (or perhaps worried) I might be a transgendered male in a female body. But as I understand it, that person wouldn’t just want to be a boy. He knows in his heart that he is one, and doesn’t feel comfortable in the female body he was given. That wasn’t quite it for me.

I was fine with my female body. I did not feel like a boy in a girl’s body; I felt like a girl, inside and out. But I still told everyone I wanted to be a boy. I have tried for over 20 years to explain why I did this, but couldn’t.

Then my mom sent me this old Christmas Wish List, and it clicked.

A translation:

Things I Want

1. Skateboard

3. Quints, you’ll find a candy cane on a table [I believe this is a bribe for Santa.]

4. Shark Attack

7. Fluorescent markers, and gray [I guarantee my dad made me look up how to spell “fluorescent”]

8. John to stop being a pest [John is my brother. This one is clearly my attempt to get in good with Santa by making him smile. It worked—I got the skateboard.]

I look at this list as a whole, and I don’t see a girl or a boy, but a child. I wanted to play outside, I wanted to draw with all the colors of the wind, I wanted games with sharks and dinosaurs and I wanted dolls (creepy, creepy dolls). I’m not saying this to let you know how cool I was—I think my use of the word “pest” takes care of that for me—I’m saying that this should serve as a reminder that kids enjoy all kinds of toys, and those toys don’t have to be SO. VERY. GENDERED. Because it can mess with kids’ heads in very lasting ways.

As a child, I saw that girls were only allowed to like dolls and the color pink. But I liked blue and dinosaurs, so I assumed that I couldn’t be a girl. And to my confused child brain, if I didn’t want to be a girl, I must want to be a boy. A – B = C.

The point isn’t that I disliked being a girl, it’s that I didn’t want to only be a girl, in the limited way it was presented to me. I wanted to be a human. I wanted to be allowed to play how I wanted to play. I wanted to play Barbies and then play dinosaurs and then ride a blue bike—because blue was my favorite color, not because it was a color for boys.

I was presented things in terms of black-and-white (or, in this case, pink-and-blue) and decided on blue. I demanded short hair and refused ruffles. Other people were confused by my hair and boy clothes—adults as well as children, and this embarrassed me. There was the teacher who didn’t know I was a girl, and insisted I line up with the other boys on our trip to the library. Children would ask me all the time if I was a boy or a girl, including once at the swimming pool while I was wearing a girl’s swimsuit. Even my female friends relegated me to the role of Ken.

Although I said I wanted to be a boy, I was embarrassed when someone thought I was one. When I learned the term tomboy, I felt relieved. Here was my place. A girl who was fine being a girl, but sometimes played “boy stuff” with boys.

The problem was, I didn’t fit in with the boys, either. I didn’t really like the way boys played—I found it boring. You can only crash cars together for so long, in my opinion. I liked to invent a story where the cars have a purpose, like running errands and making sure to stop for gas (Yep, I was a girl all right).

I don’t consider this time a phase any more than anyone else considers his or her childhood a phase. It wasn’t something I grew out of. I just learned to find my place as I got older and people stopped shoving pink down kids’ throats. By the 4th grade, girls could wear turquoise and jeans without sideways glances. They played sports and read books and no one thought it was strange. Beauty and the Beast came out and I had a Disney role model who preferred adventure over marriage. I stopped wanting to be a boy because I felt that I could be accepted as the girl I already was. I stopped wanting to be a boy once they let me back into the girl’s club.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from my own childhood, it’s to let young children play the way they want to play. If they want to play with dolls and trucks, for the love of God, let them. Give them the option and let them know it’s OK to like both. Because if we tell our tiny humans what they are allowed to like and not like, we set them up for a lifetime of feeling that they must have been made wrong.

Emily Shepard writes content for a tech company in the Bay Area. She has a new blog called Dear Me.

Related Links: