Men speak 70 percent of the time in mixed gender groups, with degrading effects on group decision-making. Women are rarely viewed as among the most powerful, influential, or relevant speakers. Their introduction of topics, or attempts to shift conversation, are frequently ignored. And their speech is routinely interrupted.

Do you have listener bias? Do you think men are talking less and women more than they actually do? Most of us do. And it results in a distorted apportionment of who actually speaks.

Gender and speech dynamics are often very heated and personal flashpoints in conversations about sexism and gender gaps. It turns out that talking in mixed gender groups—the dinner table, classroom, boardroom, parliaments—is often much more highly fraught than casual observation might suggest. When confronted with facts about male speech dominance in the public sphere and the deleterious effects of expressive imbalances, everyone suddenly become deeply passionate about how many words men and women use, who interrupts whom, and what the meaning and quality of linguistic techniques, such as hedges and interruptions, really are.

In general, people would really rather not see sexism, even when it’s staring them in the face. The idea that words and speech, as much as habits, politeness, traditions, and boys club fun might be vectors for implicit bias and discrimination that women learn to adapt to, and pay a price for, is pretty unappealing information. Stereotypes abound about women who talk more and too much, and the idea that men dominate speech, speaking up to 75% of the time in mixed gender deliberative groups is hard for some people to swallow.

Examining and revealing everyday speech interactions challenges people’s perceptions of themselves, their sense of their relationships with others, and for many men, ultimately, the degree to which they may, unconsciously, be engaging in and benefitting from behavior that has sexist outcomes.

A year and a half after writing a viral piece about gender and speech, women from all over the world continue to write to me about their frustrations in meetings, in school, and at home, and they are often thankful for the recognition of the problems they encounter trying to be heard. Many report using the article to raise awareness and start professional and personal conversations about whose voices matter.

Whenever I tweet information about these dynamics, or people raise these issues as legitimate concerns, the predictable chorus of “feminism should focus on what’s ‘really important,’ and not forget ‘Those Women Over There'” breaks out. Words such as “mansplaining” or “manterrupting” spur cries of “reverse sexism.”

There are, however, few things as consequential to women as individuals living in societies who fail to understand or meet their needs.

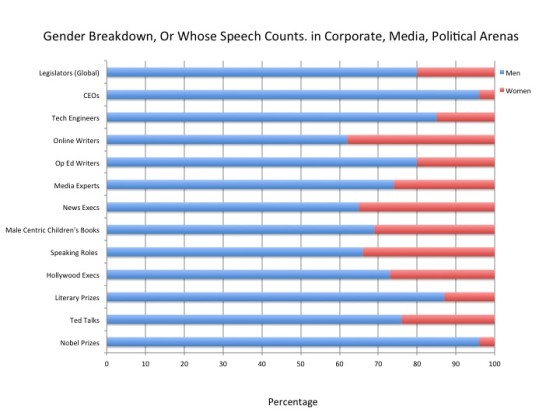

Consider this chart, showing the gender distribution of legislatures, corporate leadership, media makers, and prestigious awards. It’s a chart of whose speech is considered most valuable, which experiences matter, and whose authority is respected. It’s also a chart of collective ignorance.

Enter Gender Time, created by two Swedes, Fredrik Eklöf and Andreas Bhagwani. It is a simple app (also available for your phone) that will let you track the gender breakdown of any conversation, film, video, panel conversation, or meeting. According to the app’s website, it “helps you see and discuss normative gender patterns. Just seeing the numbers helps people self-regulate and improve.” You should download it immediately, just for fun. Anyone can use it, anywhere, although introducing the app at the dinner table potentially has the greatest disruptive effect.

The app’s next version should add interruptions in relation to volubility. Interruptions are something everyone understands, and, increasingly, organizations are looking for ways to shift conduct during meetings to account for socialization that results in women being “the silent sex.” Some organizations use talking sticks, for example, others enforce no interrupting rules. However, finding ways to minimize interruptions isn’t a panacea in a world where gender role incongruity continues to hurt women at work and in politics. For example, one study of U.S. senators shows that men who spoke more often than their peers are rated 10 percent higher for competence. Women who do the same, however, are rated 14 percent lower.

In their 500-page book, The Silent Sex, Gender, Deliberation & Institutions, Chistopher F. Karpowitz and Tali Mendleberg examine the costs of gendered speech dynamics in deliberative spaces. Women, as they note, are no longer legally barred from participating in public space in most countries. However, lower status continues to affect the ways in which women are inhibited from doing so. Women may be filling schools and the workplace, and making incursions, albeit still limited, into political and corporate leadership, but their contributions are still relegated to the invisible, quiet, and supportive scaffolding of institutions.

One of the authors’ conclusions was the efficacy of an influential procedure, the decision rule, when women find themselves in a minority, which is almost always the case in public arenas. The rule disrupts typically gendered interactions that amplify women’s silence and reduce participation and impact. When Karpowitz and Mendleberg introduced the rule that group decisions had to be unanimous (rather than plurality/majority), groups became more inclusive and more people spoke up. Women, whose voices tend to be drowned out, got a larger share of speaking time and with it more influence on decision-making. The rule creates more egalitarian conversational norms and, they believe, can have “dramatic democratic effects.”

Democratic effects are not what are going through most people’s minds when women describe their frustrations when simply trying to get a thought out without interruption. Men speak 70 percent of the time in mixed gender groups, with degrading effects on group decision-making. Women are rarely viewed as among the most powerful, influential, or relevant speakers. Their introduction of topics, or attempts to shift conversation, are frequently ignored. Their speech is routinely interrupted.

Take, for example, the entire course of Congress’ hectoring of Cecile Richards during her Planned Parenthood testimony. A deliberative body made up almost entirely of men asked questions, talked over, interrupted and defined the structure, process, and content of the five hours during which she was questioned. What happened to her reflects the same patterns as well-studied courtroom dynamics, where a woman testifying, particularly about difficult and complicated topics, is routinely unable to finish a sentence, and is thought less authoritative.

While increasing understanding of women’s lower participation in parliamentary proceedings, board meetings, and classroom debates is important, the truth is that childhood socialization continues to teach girls subordination and boys domination. Women are now educated, can vote, and work for money. And yet stereotypes and gender role adherence continue to inform self-conceptions, identity, and relationships. Gender, as Cecilia Ridgeway put it, “is more than a trait of individuals, [it’s] an institutionalized system of social practices.” One that continues, despite women’s strides, to give more credence to what men think and say. That system starts at home.

Soraya L. Chemaly writes about gender, feminism and culture for several online media including Role Reboot, The Huffington Post, Fem2.0, RHReality Check, BitchFlicks, and Alternet among others. She is particularly interested in how systems of bias and oppression are transmitted to children through entertainment, media and religious cultures. She holds a History degree from Georgetown University, where she founded that schools first feminist undergraduate journal, studied post-grad at Radcliffe College. She is currently Director of the Women’s Media Center Speech Project.

Related Links: