Despite the Instagram-worthy scenery, the women of ‘Big Little Lies’ are in pain, and rarely is succor found in their spouses.

I had no bridesmaids in my wedding party because my husband and I had no wedding party. We made the decision to stand solo at the altar for several pragmatic reasons, not the least of which was that most of our friends were as broke as we were, and we wanted to keep the cost of their attendance to a cheap hotel. Also, we had planned a ceremony lasting about 92 seconds, and it seemed silly to conduct such brief vows with people who’d be more comfortable sitting in their folding chairs.

But the most secret—at the time, even unconscious—reason for not having a wedding party was that I was in a 20-year toxic friendship with a woman for whom I’d served as a bridesmaid the previous summer, and I could see no way around asking her to be a bridesmaid in my wedding unless 1) I was willing to have the falling out we’d spent two decades avoiding, or 2) I asked no one to be a bridesmaid.

Alas, I’m a pathologically non-confrontational person.

That the friendship was toxic was not my friend’s fault. The specifics are boring and idiosyncratic, and of course, dependent on which one of us you ask, but let me be clear: I was at least as much to blame as she was, and probably more so because I had a lifelong habit of making friends with women by imitating them instead of being myself—a habit I finally began to break in college, and fully dismantled in graduate school when I found myself surrounded by women I didn’t have to imitate because we were already so similar.

I honestly didn’t know I had ever been pretending until I stopped.

This is not an argument for befriending only people that reflect you back to yourself—what a terribly myopic existence that would be. But for me, learning how to have healthy friendships with women was contingent on sloughing off some seriously malignant ideas about how women see one another. We’re all familiar with these stereotypes of the female friendship: competitive, jealous, rife with betrayal and ruthless cunning. In a world where women are still fighting to climb up from their gendered lower rung, the fight often turns inward, toward each other.

I don’t buy into these stereotypes anymore. And the experience that totally smashed those tired ideas about women to bits? Motherhood.

I’ve written before about my supportive experience in my online parenting communities, and about the all-in nature of making friends with other mothers in my neighborhood, but new mothers are still cautioned about a culture of comparison and shame more popularly known as the Mommy Wars. Stay at home or work out of the home? Attachment parenting or free range? Public or private schooling, structured or play-based learning, pro-screen time or no screen time? If you’re privileged enough to have these choices—white, middle- or upper middle-class, heteronormative—then such decisions become symbolic declarations of your own cultural hipness and in-touch values, and how likely it is that you’ll raise your kids to cure a rare disease. Or so the story goes.

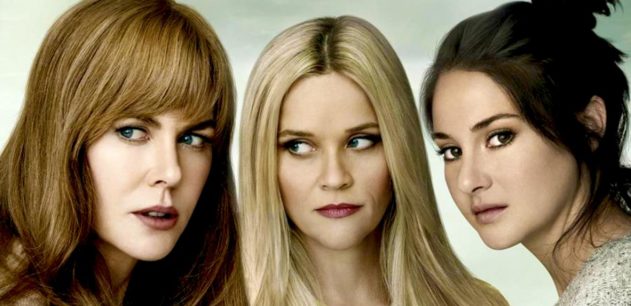

Enter HBO’s hit new miniseries Big Little Lies. Set in outlandishly upscale Monterey, California, with its backdrop of rocky cliffs overlooking sandy beaches and ocean waves, the series is ostensibly an investigation into a murder at the esteemed local elementary school, the sweetly-named Otter Bay. But the show’s true storytelling lies in the complex relationships between four mothers—Madeline (Reese Witherspoon), Celeste (Nicole Kidman), Renata (Laura Dern), and Jane (Shailene Woodley).

What first appears to be the Mommy Wars dramatized for the small screen becomes something much more nuanced: a portrayal of the internal wars women wage with themselves, often across demographics, and the potential of those private struggles to become sites of connection and—I ultimately hope as the plot unfolds—power against the patriarchal structures that created the Mommy Wars in the first place.

Take episode 4, for example, titled “Push Comes to Shove.” Celeste comes out of “retirement” (really, a forced abdication of her career as an attorney by her physically abusive and controlling husband) to help Madeline save the play she’s been producing part-time. At this point in the series, we’ve heard Madeline dismiss her job at the theater as just a hobby; she admits to Jane that she keeps her working hours low to maintain her stay-at-home status to “lord” over Renata and the other “career mommies.” Celeste, too, has been putting a good face on staying home with her twin sons in order to keep the peace in her volatile marriage.

But then Madeline and Celeste find themselves sitting on the other side of the table from Renata, who has started a petition to shut down Madeline’s play. Celeste totally slays at the meeting, stopping the petition in its tracks with only a few legalese sentences that demonstrate why she was such a successful lawyer (and why her husband probably felt threatened by her career). In the car after the meeting, Celeste and Madeline celebrate their victory, and then, in a breathless, emotional exchange, confess how it made them feel to accomplish something outside of their mothering. “I want more!” Madeline shouts, beeping the horn repeatedly.

Renata, too, struggles with her choices. She fronts as a high-powered businesswoman with equally powerful friends, but agonizes over her inability to help her daughter, Amabella, who is being bullied at school by an unknown assailant. In episode 6, “Burning Love,” Amabella continues to shut Renata out, and Renata feels increasingly desperate and insecure in her mothering. Petition-happy, she circulates a new call for Jane’s son, Ziggy, who has been accused of the bullying, to be suspended from school. Jane confronts Renata at Otter Bay and somehow ends up poking her in the eye.

It’s almost parody at first: the wealthy businesswoman treating the poorer, new family in town like garbage in need of taking out; the poorer mother revealing herself to be scrappy and resourceful and not to be fucked with. But then, Jane, a rape survivor who feels terrible about her own capacity for violence in defense of her son, shows up at Renata’s literal glass house to apologize.

“The truth is, I finally realized I’ve been feeling exactly what you must be feeling. There’s nothing worse than your child being victimized, right?” Jane says to Renata.

“You think you’re at your wits’ end,” Renata says, not at all unkindly, instead reaching toward Jane’s empathy in an unexpected moment of her own vulnerability. “My daughter’s the one getting hurt, and I can’t stop it.”

“I’m so sorry,” Jane says.

“Me too,” Renata says.

God knows the problems of the Otter Bay parents are some of the most luxurious any parent could imagine. But despite the Instagram-worthy scenery—those cliffs, those houses, those porch fireplaces that I will forever associate with wealth beyond my wildest dreams—the women of Big Little Lies are in pain, and rarely is succor found in their spouses. Most of the time, that succor is found in friendship with women predicated not on parenting styles, but on compassion for one another’s unwinnable lives.

My daughter was almost 2 when I heard that my former friend—my childhood friend, the woman I did not treat as she deserved because I did not treat myself as I deserved—was pregnant with her first child. By then, I had experienced a high-risk pregnancy and terrifying labor, the challenges and rewards of breastfeeding, the growing pains of a marriage after kids, and the corrosive guilt that chafes and whittles and erodes mothers daily, no matter their choices, and in many cases, because they have none. I knew my former friend would experience some, if not all of these things, too. And though we hadn’t spoken for years by then, I felt closer to her than I ever had.

So maybe this is a missive to her, and to all mothers who worry that to be seen as a parent is to be judged. I am making mistakes, too. I am not always happy. I don’t know how to win the war within. But I am on your side.

Amy Monticello is an assistant professor at Suffolk University. Her work has appeared in many literary journals, and at Salon, The Rumpus, and The Nervous Breakdown. She currently lives in Boston with her husband and daughter. Follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Other Links: