When a woman conceals the first trimester of pregnancy, who is she trying to protect?

These days when I leave the house, I take the refrigerator with me. For a three-hour-long journey, I pack two peanut butter sandwiches, two yogurts, an apple, two oranges, crackers, water, and ginger ale. For a shorter trip — to the bank, let’s say — I’ll make a go of it with only one sandwich, one yogurt, and one piece of fruit. This is not my lunch, mind you: I pack all this up after having eaten a full meal. My snacks have become my security blanket and my lifeline.

At 13 weeks pregnant, I shovel food into my mouth and it disappears. An hour after eating a solid meal, I am ravenous. Unlike in my pre-pregnancy life, where hunger arose and I had time to decide what and where I wanted to eat, now, if I fail to eat within three minutes, I risk throwing up. It’s a little like getting to the beeping alarm code before the siren goes off and the police are on their way. I shouldn’t even call this hunger. It’s more like trying to stop up an ever-expanding hole.

I eat on the subway, on the street, at my desk, in bed. I’ve made a habit of forcing the street-food guy to turn on the oil to cook me fries at 10:30 a.m. Every night as my husband and I are watching “Homeland”—I wouldn’t recommend this for pregnancy viewing—I usually start to moan. All I really want to do is sleep—early pregnancy is notorious for causing exhaustion that feels utterly obliterating —my husband pauses the episode and puts our emergency food plan into action. He pulls me into the kitchen as though we were seeking shelter during a bomb scare.

Is this the part I’m not supposed to tell you?

Like 50 to 80 percent of women in their first trimester, I have “morning sickness,” which anyone who has ever had it knows is the most evil misnomer of all time. “Morning sickness” makes it sound like you have a nice little hurl with your morning decaf and go on your merry way. It makes it sound like the immense flood of hormones surging through your system is no more disruptive than a canker sore.

In fact, morning sickness is much more akin to having a three-month-long stomach virus that you are forced to keep a secret. (Poor Kate Middleton had no choice about the secret — hurl enough and you get hooked up to an IV in the hospital. What she is experiencing, for the second time, is nothing short of hell — and as a friend who suffered through it herself said, “No amount of money or fame can save you from it.”)

Before getting knocked up, I respected the veil of secrecy around the first trimester, but I had no idea how difficult it would be to live it. This code of silence lasts until the 12th or 13th week, when the pregnancy is deemed “safe” and “viable” and you are free to announce it to the world. Until then, you have to struggle through whatever comes up — emotionally or physically — with your partner (and parents or siblings, if you’ve told them) alone.

From what I can gather, this code of silence is meant to protect you, the pregnant woman, from the (supposed) shame of reporting back to your community that this pregnancy is not to be. Since this early stage is deemed the most risky, tradition holds that it’s best to conceal your pregnancy from everyone, and to present it to the world once you are (again, supposedly) no longer in danger, no longer puking or exhausted, with a bump and a glow to show for it.

Before I got pregnant, the people who announced their pregnancies on social networking sites—or told near-strangers in the real world—at six or seven weeks appalled me. Are they crazy? I thought. What will they do if something goes wrong and they have to tell 1,000 people—many of them virtual strangers—that they lost the baby?

Now, I sympathize. I still cringe to think of what they, or I, will have to go through in the event that disaster strikes—one in five pregnancies results in miscarriage— but what I’m putting myself through by observing the code of silence may not be the solution either.

In my family, losing a baby was almost as normal as carrying a baby to term. My sister had a miscarriage and then an ectopic pregnancy before giving birth to two children, three years apart. My mother had two stillbirths between me and my sister —one at 24 weeks, one at 23, well into the time when she was identifiably pregnant and “out of the woods.” I have always known that my birth—five weeks early, after my mother spent two-thirds of her pregnancy in bed to stave off near constant contractions—was somewhat of a miracle. I have long viewed pregnancy with terror and the humming knowledge that anything could go wrong.

When I told my parents and sister that I was pregnant, I felt myself keeping my excitement somewhere across the room.

“Not getting excited now won’t protect you later if something goes wrong,” my mother said. “Enjoy it.”

But after spending many years mourning the two babies she lost, my mother had other advice too: “Tell as many people as you like. Tell them now.”

“If something does go wrong,” she told me, “you’re going to need your friends. You’re not going to want to lie about how you’re feeling to everyone in your life.”

Despite being married to a wildly supportive, thrilled father-to-be, I have found these last few weeks to be some of the loneliest of my life. Much of this is because I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time alone in our apartment, feeling awful. But it is also because I am by nature an over-sharer—it is hard for me to keep anything to myself for long. Although I’ve told most of my closest friends about the pregnancy, we no longer live on the same continent—my husband and I moved from Brooklyn to Vienna, Austria, right before conceiving—so the support comes in fits and starts on Skype or email. It’s a far cry from an afternoon tea or the offer of a visit or a bland home-cooked meal. Since we’ve only been in our new home for a few months, it is hard to tell very new friends—acquaintances, really—that you’re canceling plans (again!) because you’re puking and drained and frightened, and probably will be for some time. This only adds to the isolation. I don’t like to fib, and since very little else has been going on in my life, I’ve had little to report.

Other than a steady stream of TV, the love of my husband, and a constant intake of food, I have needed nothing more than the support of my community—and this is exactly what you don’t get when you stay silent.

I still remember one first-trimester early sharer on Facebook bemoaning how sick she felt and how often she was puking—and the 40 or so replies she got from women in her circle offering her encouragement and advice (eat ginger, drink cardamom tea, wear wrist bands, etc.). At the time I thought her behavior performative. But I have to admit that there have been several times during these early weeks when I’ve had to stop myself from asking for help on that very forum, or from random colleagues at work—and a small part of me has felt ashamed for having to hide how I’ve been feeling, like there’s something wrong with me. I’m getting the message that I have to conceal the biggest, most debilitating, most painstakingly natural thing going on in my life right now.

It is, of course, a matter of personal preference how and when anyone divulges a pregnancy. I’ve told my closest girlfriends and my family, and I’m fortunate in that I could tell others without real social stigma, if I wanted to—many women need or want to hide their pregnancies in order, if not to keep their jobs, then to continue to fit in at work. A friend who works for a big-city police department forced herself, despite horrible nausea, to hang out in bars with her colleagues because it was part of the culture of her job and her absence would be a signal she wasn’t ready to send. She emptied beers in the bathroom and filled them with water.

But even in less extreme cases, the idea that you’ll keep early pregnancy hidden is an expectation, a norm. These first few weeks, I’ve felt obligated to cloak myself in a veil of secrecy and silence — a silence that is self-created, but culturally mandated. On the simplest level, I would like to not hide how sick and tired I feel and to not lie about why I’ve cancelled so many plans. I can’t pretend to have the stomach flu for three months. I would also like some help: the hard-earned advice my mom friends have given me (eat crackers in the middle of the night when you get up to pee; keep juice and yogurt by the bed) has been more valuable than anything I’ve read in a book or have heard from my doctor, but I feel like they are passing me these secrets under the table while no one is looking. Who knows what the other legions of mothers would tell me if I could ask anyone I wanted without worry?

I don’t want to imply that pregnancy is terrible, or that we should encourage it to take over our lives. But the first-trimester charade is isolating, and sometimes insulting; one Pregnancy App tried to teach me how to “have morning sickness in public: Pretend you’re looking for something deep inside your purse—then snap it shut and discard.” Why does early pregnancy have to be a stiff-upper-lip acting job? Can’t it just be a big fat announcement of a wondrous and difficult biological truth?

I wonder whose anxiety we’re trying to protect in concealing these first few difficult months. Is this supposed to be for my sake? Are we trying to protect me from the embarrassment of admitting that I can’t go 45 minutes without eating and am gaining weight at a rapid clip? That I spend most of the day crying and moaning on the couch? That I’m afraid of losing the pregnancy but can’t fathom that this debilitating state of being has anything to do with an actual baby? Are we really trying to save me from having to share the news if I have a miscarriage? Or are we trying to protect our culture from admitting that not all pregnancies are beautiful and easy and make it to term, and that the loss can be absolutely devastating?

As we all know, people say the most careless things to women who’ve miscarried—usually to the tune of “you’ll have another one” or “you weren’t even that far along.” Our fear and unease around death—especially when it comes to babies—is bottomless. When my mother lost a baby girl at 23 weeks a year after losing a boy around the same gestational week, the doctor wrote in her file, “Mother in good spirits.” I wonder if this would happen if we were more honest about the reality of being pregnant, or not being pregnant anymore.

The most alarming thing I’ve heard from friends who’ve had miscarriages is their surprise (only upon miscarrying) at hearing about how many of their friends, aunts, cousins, sisters, mothers, and grandmothers have had them, too. If miscarriages are so common, why do we hide them behind a wall of shame and silence? If women could announce their pregnancies immediately, wouldn’t we learn that a pregnancy is truly awesome and terrifying and precarious and unknown — that anything can and does happen, and that women deserve all the love and support and understanding that comes with the act of trying to make another human being?

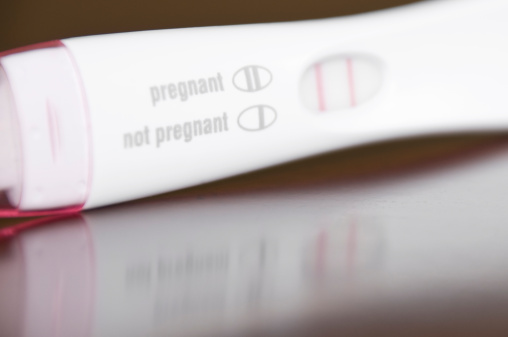

Of course none of this is simple. I’ve had these thoughts for weeks, but it is only now—at the magical 13th week, after seeing what looks like an actual baby with arms and legs and a heart dancing around in my very own body—that I’m willing to air this beyond private conversations among friends. I could blame the nausea that has had me pinned to “The Good Wife” (ironically) during most of my waking hours, but I know that it’s more than this, and that perhaps I am no different from anyone else who wants to keep part of her life—the momentous, nascent part—to herself. Given my mother’s experience, I’m not sure whether I’ll ever feel that this pregnancy is “safe.” I, too, fear having to retrace my steps with heartbreaking news. I, too, want some semblance of control over who enters this sphere of my life. Women’s choices so often tread a very thin line between the private and the public, and it is perhaps because these first few months can be private—unless you’re royalty—that we try, even at great sacrifice, to keep them this way.

Abigail Rasminsky has written for The New York Times; O: The Oprah Magazine; Brain, Child Magazine; The Morning News; The Forward; Archipelago on Medium; and Dance Magazine, among other publications. She is a graduate of Columbia’s MFA Writing Program and lives in Vienna, Austria, with her husband and daughter. More at abigailrasminsky.com. You can find her on Twitter @AbbyRasminsky.

This originally appeared on Medium. Republished here with permission.

Related Links: