I define bossy to mean carrying a ferocious work ethic, being a person of conviction, and having a clear vision of how to solve problems.

Much digital ink has been spilled over the Ban Bossy campaign—both for and against the campaign.

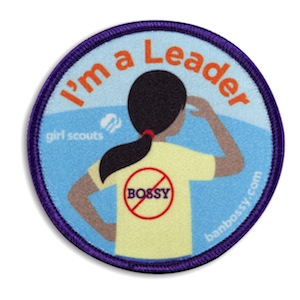

I honestly felt a little betrayed by the Girl Scouts when I read about its new merit badge associated with the campaign. Being a lifelong Girl Scout helped me build confidence in who I am—including being called bossy. The Girl Scouts’ familiar circular patch shows a young woman with her back to us, looking out onto the horizon with the word “Bossy” in a strikeout logo, and “I’m a leader” along the top of the badge. My first reaction was: Why didn’t they just have the word “Leader” on her back, as opposed to reinforcing a potentially negative label?

Yet the merit badge’s image is not completely unfamiliar to me. Scouting has helped me navigate all sorts of unchartered spaces in my life. The Girl Scout motto is “be prepared”—and when it came to school or work life, that motto has been my internal compass. Like a real-life Leslie Knope with a slew of heavy binders, I was prepared for any situation or contingency, and had data and evidence to support my logic, often neatly indexed with color-coded dividers.

Did such an approach cause me to be called “bossy”? You bet. But since “bossy” and “prepared” were somehow linked in my mind, it was simply a part of who I was and still am.

I wonder if a person’s reaction—love or loathing—of the term “bossy” says more about how each person defines the word bossy, rather than the effect the word has on us.

I define bossy to mean carrying a ferocious work ethic, being a person of conviction, and having a clear vision of how to solve problems. But this is probably the result of having spent all of my 35 years not accepting bossy as a negative term. Being bossy didn’t preclude me from also respecting other people’s emotions, being self-reflective, taking constructive criticism, or being a strong team player. I believe it makes me more competitive in the workplace, helps me be a better team member because I will defend my teammates against attack, and it makes me a strategic staff person because I know how to tenaciously advance a project.

I find the stories told by famous women like Tina Fey to be deeply resonant. I laughed through every sentence of her book Bossypants because, like Fey, I managed to survive a brutally nerdy youth. I was a social outcast and channeled every last ounce of angst and bullying into fuel for my competitive spirit, which helped me survive adolescence and get out into the world.

It is a laudable goal, to want to remove language that we suspect might be damaging for young people. To be able to protect a young woman from losing confidence at a crucial age is an attractive campaign, particularly if it can successfully prevent harm. I think for some people—like Sandberg—there are words that stay with us our entire lives that sting in such a memorable way that we believe it destroyed fragile opportunities.

But for some of us, those same words have a very different effect. We had to figure out some way to survive, so we aggressively reclaimed labels like bossy and integrated them into our identity.

I understand and respect the effort behind what Sandberg and the Girl Scouts are trying to do, but I don’t know if removing a word will help a young woman discover who she is or help her build a strong internal sense of self. Words mean different things to different people, and the power behind certain words varies wildly.

We can choose not to use a word or we can choose not to let a word chip away at our self-esteem. The trick is to develop a clear vision of self and be aware of what bolsters or damages that poise. And just as the Girls Scouts taught me, be confidently prepared—for whatever life throws at you.

Tanya Tarr lives in Texas, where she helps fight for public education. She haphazardly blogs at http://becomingtexan.

Related Links: