Many of the objections to “Yes Means Yes” come down to a discomfort with one thing: shifting the onus from survivors of sexual assault, mainly women, to perpetrators, mainly men.

Last month, California passed a new law requiring state schools to use a “yes means yes” standard during campus sexual assault adjudication processes. Other states are following suit. This law, further strengthening a culture of consent, has elicited confusion, and in some, panic.

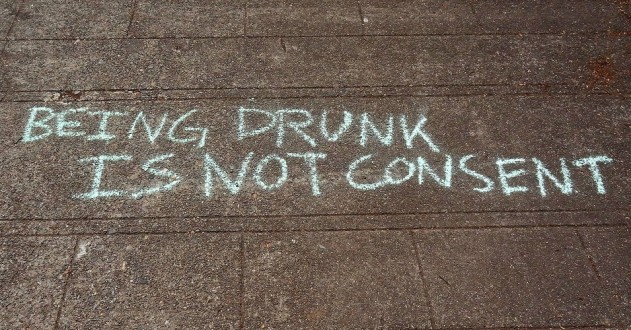

The law, the first of its kind in the United States, says first, that a person not physically fighting back against an aggressor or being silent is not consent; second, that people who are under the influence of alcohol or drugs, asleep, or unconscious are incapable of consent; third, consenting to one form of sexual activity does not mean consent for all sexual activity. The law only applies to the way schools deal with sexual assault cases.

“Given how poorly it’s worked,” explained Katha Pollitt earlier this week, “maybe we needn’t cling to the ‘no means no’ standard, under which a woman is presumed ready for action even if she lies there like lox with tears running down her cheeks, too frozen or frightened or trapped by lifelong habits of demureness to utter the magic word.”

The system we have in place has been failing victims of assault, especially when it comes to college campuses. More than 85 schools are now being investigated for failures to handle sexual assault cases involving students, including Berkeley, Occidental, and USC, just in California. Nationwide, fewer than 2% of college rapists are ever sanctioned.

The standards we rely on, on campuses and in courtrooms, continue to ignore decades of research about sexual assault, survival responses, and the behavior of serial predators. They also perpetuate dangerous rape myths, such as the notion that rape is forcible and violent. Laws that depend on evidence of physical brutality are laws that ignore the reality of women’s lives and experiences and holds them to a male standard that is irrelevant and unjust.

These are standards, historically based and evolving over time, written by men, based on men’s ways of being and knowing. These standards are inseparable from male sexual entitlement and the idea that boys and men cannot control themselves.

Kneejerk responses to a “yes means yes” standard of consent often fall back on one or more of these myths:

Myth #1: “This is a radical, new idea.”

Affirmative, enthusiastic, consent is not new. The concept, and the ideas that underlie it, have been around for a while. For example, Antioch College, in the face of much derision, introduced the idea in terms of campus life, 23 years ago. As a former student at the school, J.M. Bishop, now a sex educator, recently explained, “Emphasizing overt mutual consent embedded within a context of ongoing communication can be framed as empowering—it’s raising their expectations. Calling this radical or ridiculous just shows how low the bar is set around human behavior in some quarters.”

In 1992, Canada, the country, adopted an affirmative consent approach in their law. In 2008, Jaclyn Friedman and Jessica Valenti’s book, a compilation of essays, Yes Means Yes: Visions of Sexual Power and a World Without Rape, significantly shifted the conversation and brought it into the mainstream culture in unprecedented ways. Everything you wanted to know about “Yes Means Yes,” but were afraid to ask can be found at their eponymous blog.

Myth #2: “Yes Means Yes” turns most sex into criminal rape and spoils real sex.

“It means that people who want to have sex have to sign a contract or use an app.” It does not have anything to do with criminal prosecution. Nothing in the statute even remotely touches on the shape or form of the communication between actors. It doesn’t require a written statement or even a verbal “yes.” What it does is make clear that silence and/or impairment do not constitute consent.

Myth #3: Boys and men will be unfairly penalized for easy misunderstandings and miscommunications.

Thomas MacAuley Miller, writing at Yes Means Yes, broke this idea down with well-sourced analysis several years ago. “The notion that rape results from miscommunication is just wrong,” he explained. “Rape results from a refusal to heed, rather than an inability to understand, a rejection.” So this fear, like many swirls around the spectre of false accusations, which hits parents, alumni, and administrators, all part of our larger culture, very hard.

It is worth exploring why this is the case since so many more people are being raped, with ill effects and consequences, than are being falsely accused. Rates of false allegations of rape are well understood by criminologists and other social scientists to be between 2% and 8%, in line with false allegations of other crimes. And yet, students, parents, and campus police continue to think that number is closer to 50%. Interestingly, the longer a police officer has worked on sex crimes, the less likely he or she is to believe in false claims. A majority of detectives with between one and seven years of experience believe that 40% of claims are false—in some cases that number is as high as 80%. But among officers with more than eight years’ experience, the rate drops precipitously, to 10%. There are people whose lives have been and are being ruined by rape that we, as a society, continue to ignore.

Myth #4: “The law ignores situations when both people might be drunk.”

On the contrary, the law understands this reality exquisitely well. Most young men are not rapists, and studies repeatedly show that predatory people explicitly target vulnerable people, particularly young women, particularly with alcohol. The “both people are too drunk to know what they are doing” scenario is a rare one and a man’s alcohol intake actually doesn’t affect whether or not he crosses lines he shouldn’t.

A study of sexual assault and the role that alcohol plays, Blurred Lines: Sexual Aggression and Barroom Culture, conducted earlier this year by researchers at the University of Toronto and the University of Washington found that there was no relationship between a man’s aggressiveness and his level of intoxication. What it did find was that intoxicated women were targeted with malice by men who understood what they were doing. The researchers concluded, “people should stop believing that [Robin Thicke] song. The lines really aren’t that blurred.”

Nine out of 10 sexual assaults on campus are perpetrated by serial offenders who use alcohol as a weapon. However, what if both people are drunk? As Caroline Heldman wrote last week in response to a backlash at Harvard, “…intoxication is never an excuse for committing a crime. A useful analogy here is a drunk driver who hits someone. We do not give the driver a free pass because he was drunk, or say that it’s a ‘complicated’ situation because his judgment was impaired. The same applies to drunk students who initiate sexual activity with a person who is incapacitated and thus not able to consent.” I’m with her in asking, does this logic extend to other crimes?

Myth #5: “‘Yes means Yes’ ‘fixes’ a problem that doesn’t exist. Why can’t a person just say ‘no’ or fight back?”

No is not always an option and, for the most part, women understand the dangers of saying no when they are not interested in sex. A whole host of factors, ranging from socialized and gendered politeness norms to fear of being hurt, govern verbal and physical responses during sexual assaults and encounters. Thinking that people being sexually assaulted can “just say no,” or engage in a fight just displays a certain, clueless privilege.

Myth #6: “This law, and others like it, will change everything about how we prosecute rape claims.”

If that were true, I’d be forced to ask: That would be bad why exactly? Because women lie and innocent lives are ruined? It is an overwhelmingly clear fact that the raped and not rapists are shamed in our culture. That the survivors of rape suffer—emotionally, physically, materially—long after their assaults.

It’s also a demonstrable fact that institutions don’t care to acknowledge how many rape survivors’ academic lives are degraded or ruined as a result of assaults on campuses. Other than engage a broader community in important conversations, this law will do nothing to change the generally deplorable way many police officers, judges, and juries continue to deal with sexual assault. “Yes Means Yes” standards for schools, for example, won’t do anything to directly put a dent in our 400,000-plus backlogged rape kits or million-plus mis-categorized and missing rape cases.

Not one of the many people I know involved with the Title IX movement, or in making sure that “Yes Means Yes” gains traction broadly, is remotely interested in micromanaging sexual interactions or falsely accusing anyone. There are legitimate questions about how this statute looks in execution, but those two are not among them.

Mainly, this statute is a stepping-stone to greater awareness and education—for everyone, especially parents, administrators, coaches, and other people with authority. “Yes Means Yes” is a crucial step away from a culture of coercive sexuality. One that has historically favored the interests of the powerful, entitled, and abusive, most of whom, for cultural and historical reasons, have been men.

For parents concerned about sons, the best thing they can do is support comprehensive sex education in middle and high school, talk to them about sexual entitlement, counsel them about consent and alcohol abuse, and explain what rape is, in the same way that parents of girls should. And, for boys, probably discourage them from joining fraternities. Studies show that men in fraternities are three times more likely to rape.

Lastly, moving “no means no” to “yes means yes” touches directly on another important issue: women’s active, equal, participation, and pleasure in sex. The prioritization of male sexual desires, and coercion to fulfill it, is a global truth.

A study conducted earlier this year looked at heterosexual anal sex, increasingly practiced, and found that “anal heterosex appeared to be painful, risky, and coercive, particularly for women, while males spoke of being expected to persuade or coerce reluctant partners.” The researchers concluded, as have other studies, people “rarely spoke of anal sex in terms of mutual exploration of sexual pleasure.”

If you ask me, despite the monumental effort it took to get us to this point, it’s still too little, too late. The lessons of “yes means yes,” ideas about consent, agency, and how one should treat another person’s bodies and desires, should be fundamental ones. They can’t start too early.

In the end, what much of these objections seem to come down to is a discomfort with one thing: shifting the onus from survivors of sexual assault, mainly but not by any means exclusively, women, to perpetrators, mainly men.

As Amanda Hess put it, “If you think it’s easy for a person to just say no, then why would it be so hard for his or her partner to just ask?” Why does that worry people so much?

Soraya L. Chemaly writes about gender, feminism and culture for several online media including Role Reboot, The Huffington Post, Fem2.0, RHReality Check, BitchFlicks, and Alternet among others. She is particularly interested in how systems of bias and oppression are transmitted to children through entertainment, media and religious cultures. She holds a History degree from Georgetown University, where she founded that school’s first feminist undergraduate journal, and studied post-grad at Radcliffe College.

Related Links: