Once I begin thinking that I could never be like those guys over there, it becomes much more likely that I’ll act exactly like them. Recognizing that I could act like that gives me the room to make the ongoing decision to act differently.

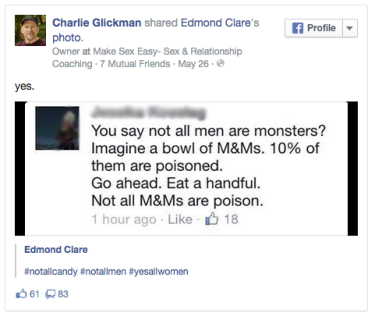

In all of the recent conversations about male privilege, violence against women, and misogyny, there’s been a lot of debate about “not all men.” When guys are confronted with the many ways in which men hurt, harass, and abuse women, it’s a pretty common response for us to say, “I’m not like that.”

Many of us want to be one of “the good guys,” the ones who don’t act like jerks, who don’t harass women or commit assault. Other people have explained why it doesn’t make sense for women to assume good intentions, and of course, some men jump to say that they aren’t like that and deserve better.

I get it. I really do. For more than half my life, I’ve had women tell me that I’m not like most of the other men they know. I’ve never really fit into the standard definitions of masculinity and I’ve been like this ever since I was a kid. I’ll admit there was a time when my ego enjoyed the positive reinforcement, especially since it helped me feel better about the fact that I wasn’t like most guys.

But then I realized something important.

While I might be less capable of physically forcing someone to do something than many men are, I can exert male privilege in a lot of other ways. I can assume that my opinions are more valid than the woman I’m speaking with, I can talk over her, interrupt her, or ignore her, and a lot of people won’t even notice. I can harass someone, not take no for an answer, whine and cajole her in order to make her feel obliged to comply with my demands.

I can slut-shame someone for having sex, call her a prude if she turns me down, and I have much more freedom to have sex without repercussions. I can safely assume that in most occupations, I’ll be paid more. I can walk around at night with a lot less fear. I can take up more space than women, both physically and energetically, and usually get away with it.

There are dozens of ways in which I can benefit from being a cisgender man, whether I want to or not.

It’s those last six words that make all the difference to me. There are ways in which I don’t have a choice about the privilege that accrues to me, and in those cases, there’s not much difference between other men and me.

There are also ways in which I have some influence about the privilege I receive. In those situations, as soon as I start believing that I’m not like those “other men,” I’ve taken the first step down a very steep, slippery slope. Once I begin thinking that I could never be like those guys over there, it becomes much more likely that I’ll act exactly like them. Saying that I’m not like that would allow me to become complacent about my privilege and my internalized sexism and misogyny. Recognizing that I could act like that gives me the room to make the ongoing decision to act differently.

When we say that “I’m not like that,” we render those guys as other. Rather than seeing our shared humanity, we demonize them. Rather than seeing the ways in which sexism is trained and shamed into each of us, we call them evil and stop looking at ourselves. And rather than reaching out to them to help them move in a positive direction, we discard them so that we can be “not like them.” I don’t see how that does anything other than perpetuate the cycles that I so passionately want to stop.

I refuse to be one of “the good guys” because I know that I have to keep making choices about how I want to act. I refuse to be one of “the good guys” because I know that I’ve said and done things that I’m not proud of. I refuse to be one of “the good guys” because I don’t want to widen the chasm between me and the men who have the potential to change. And I refuse to be one of “the good guys” because I know that I will make mistakes and it’s so much harder for me to be accountable and make amends when my identity is challenged. It’s a lot less difficult to move forward when I’m not weighed down by the need to rethink who I am.

Men will often try to protect themselves from women’s anger by trying to minimize it or make it go away. We do that because we’re scared of it, because it triggers us, because it brings up our fear and our shame. But it almost always sends the message that we don’t think that women’s anger is valid or reasonable. For most men, it takes a lot of practice to be able to hold space for women’s anger without getting lost in our reactions, especially since many of us were never taught the skills of emotional self-regulation and shame resilience. But when we try to make women’s feelings disappear, we make things worse.

When we learn how to listen to them with fierce compassion instead of defensiveness, we make things better. As a relationship coach, I’ve seen this over and over. (And no, that’s not limited to women’s emotions, but that’s the focus of this post.)

So when I hear a woman make a sweeping statement about men, I try my best to hold space for her feelings and her experience without telling her that she’s wrong, or that she’s crazy, or that I’m not like that. I don’t always manage it, especially in online interactions, but I’m getting better at it. And part of how I work on it is by not letting myself fall into the trap of thinking that I’m one of “the good guys.”

So don’t call me a good guy. Just let me work on being the best person I can be, with all of my flaws and limitations. And when I don’t live up to my expectations or when I do something that hurts you, let me know so I can fix it. Trust me—it’ll be a lot easier for you to do that if you’re not caught up in thinking that I’m one of “the good guys,” too.

Charlie Glickman is a sexuality educator, occasional university professor, writer, blogger, and coach. In addition to working with individuals and couples to help them create happier sex lives, he teaches workshops and classes on sex-positivity, sex and shame, sexual practices, communities of erotic affiliation, and sexual authenticity. Find out more about him on his website (www.charlieglickman.com), on Facebook (www.facebook.com/drcharliegli

This piece originally ran on CharlieGlickman.com. Republished here with permission.

Related Links: