Since Eve first realized she was naked and scrambled to cover her shame with fig leaves, feminists have been divided over the question of how to return dignity and humanity to the female body.

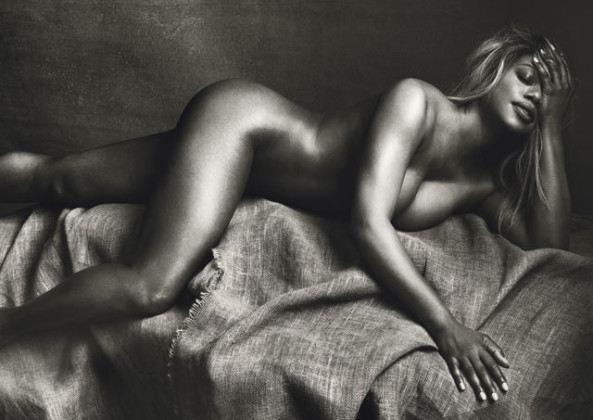

It was apparently a fraught decision for the avid bell hooks reader, but after a bit of back and forth the popular Orange Is The New Black actress, feminist, and trans activist Laverne Cox accepted an offer to pose nude in Allure magazine.

Like a lot of sex-positive feminists, I was expecting the TERFs and SWERFs to come out in full force to raise hell at this electrifying decision. But in fact the only (muted) gasps of She’s objectifying herself! were confined to Huffington Post commenters and my Facebook feed and were mostly absent from the wider feminist blogosphere—testament to the enormous respect Cox has come to command among feminists in recent years.

Imagine the response, though, had it been, say, Jezebel editor-in-chief Emma Carmichael or Guardian feminist writer Jessica Valenti—both cis white women—who’d opted to do full nudes in a manner they deemed subversive or representative of women’s underexplored and long-repressed sexual subjectivities.

Everyday Feminism, Upworthy, and the entire rank-and-file of the No More Page 3 campaign would almost certainly lose their shit.

How has mainstream feminism swung from its enthusiastic alliance with sexual liberationists during the Second Wave to now suppressing disapproving tuts when a popular feminist icon opts to free her nipples in front of a camera?

The answer, in my view, lies not in any increase of feminist puritanism, but in how the idea of objectification, for centuries a key analytical concept in the women’s equality movement, has become so stretched that it’s now almost empty of analytical value. Paradoxically, this stretching now simultaneously functions to constrict the sexual agency of women themselves.

The dictionary denotation of objectify obviously involves reducing a person to the status of an object lacking human agency or subjectivity. Even this strict-constructionist understanding of objectification has far-reaching scope as a critique of the representation of female bodies. We all are more than acquainted with advertisers’ ubiquitous tactic of literally fusing a female body shorn of any sign of human subjectivity with a physical object for capitalistic consumption, like this.

And this.

And more recently, this.

But liberal philosophers interested in women’s rights have been expanding the notion of objectification beyond a literal identification with physical objects as far back as Kant in the 1700s. For Kant, any sexual relationship outside monogamous marriage was objectifying, and the only context in which sex did not reduce people to a means for pleasure rather than as ends in themselves was one where two people mutually owned each other through the legal enforcement of matrimony.

More modern feminists have veered away from this idea of non-objectification=mutual emotional property-holding while still holding on to Kant’s idea that objectification involves using people as solely a means to an end. The philosopher and feminist Martha Nussbaum enumerated these features of objectification in the 1990s:

- instrumentality: the treatment of a person as a tool for the objectifier’s purposes;

- denial of autonomy: the treatment of a person as lacking in autonomy and self-determination;

- inertness: the treatment of a person as lacking in agency, and perhaps also in activity;

- fungibility: the treatment of a person as interchangeable with other objects;

- violability: the treatment of a person as lacking in boundary-integrity;

- ownership: the treatment of a person as something that is owned by another (can be bought or sold);

- denial of subjectivity: the treatment of a person as something whose experiences and feelings (if any) need not be taken into account.

Andrea Dworkin, the famous anti-porn crusader, saw the marker of objectification as being when a human is “turned into a thing or commodity, bought and sold.”

But the problem with all of these loose-constructionist understandings of objectification is that they are too broad: They pathologize many interactions we would usually deem benign. Dworkin’s emphasis on the commodification of the use of bodies, for example, could apply equally to people who sell any form of physical labor, like digging holes or stacking shelves, on labor markets.

Nussbaum herself noted that certain kinds of instrumentality were clearly not exploitative in certain contexts: “If I am lying around with my lover on the bed, and use his stomach as a pillow there seems to be nothing at all baneful about this, provided that … I do so in the context of a relationship in which he is generally treated as more than a pillow.”

But modern articles on objectification on mainstream feminist websites have almost entirely lost this nuance and concern with exercise of human agency in contexts of power relationships. Popular talk often conflates objectification with simple nudity or even just finding people attractive in general.

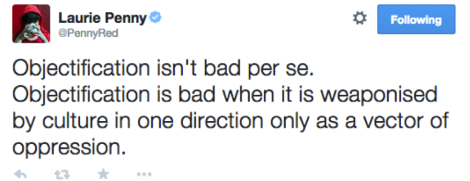

And so we get feminist writers who, for example, berate straight women for noting and enjoying the physical attractiveness of male soccer players, and conceptually fuzzy, sorry-not-sorry tweets like this one from New Statesman writer Laurie Penny after she publicly salivated over male ballet dancer Sergei Polunin’s “Take Me to Church”:

Thus we have a culture of feminist discourse where it’s normal for women to attack other women who choose to appear nude, and where every public visual exploration of female sexual subjectivity risks being denigrated as objectifying—even in cases like the Laverne Cox nudes where the choice to appear nude was clearly intended as a subversive one. So much conceptual stretching has happened around the notion of objectification that we have effectively boxed ourselves in and taken away our ways of representing, analyzing, and deploying women’s own sexual agency.

Since Eve first realized she was naked and scrambled to cover her shame with fig leaves, feminists have been divided over the question of how to return dignity and humanity to the female body. Sex-positive feminisms think the answer lies in ridding ourselves of the albatross of shame surrounding nudity and sexuality full stop, while anti-porn and Nordic-model feminisms see the answer in eliminating venues where women appear nude or sexualized.

But the mostly-respectful reception of Laverne Cox’s Allure spread indicates that maybe, just maybe, the feminist sex wars might be giving way to a more nuanced, context-dependent understanding of objectification.

And for that among many other reasons, Ms. Cox, we love you like crazy.

Samantha Eyler is a freelance American writer, editor, and translator based in Medellín, Colombia. She has written about politics, immigration, Latin America, and social justice for publications such as NACLA and the New Statesman. You can follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Related Links: