In this way, I want #MeToo to act as a mirror. For men all over the country, all over the world, to listen to not only what women experience, but to how women constantly adapt their daily lives to avoid getting groped or followed or belittled.

One night during a particularly ugly bout of verbal abuse from my then-partner, I finally asked why he thought it was OK to talk to me that way. “I don’t know,” he said. Then he thought for a second. “A lot of it is the way you dress.” Like a lot of 23-year-old girls, I had a penchant for the backless, romantically draped tops that lined the racks at Charlotte Russe. But if it would change the way I was being treated, I could adjust. I stopped wearing those clothes around him. Not long after, one of his friends sat down on the sofa next to me and eyed my chunky sweater. “You dress like a mom of three,” he said.

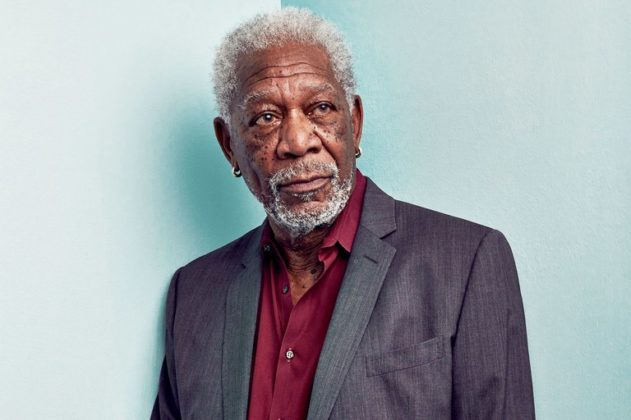

When I read the recent allegations against Morgan Freeman, specifically how the women would “combat the alleged harassment on their own, such as by changing the way they dressed,” I remembered two things. First, that changing the clothing you wear is not a reliable defense. My former partner continued his behavior even after my style overhaul, and years earlier, when I was assaulted in college, I was covered from head to toe. Second, that it is always women who have to adjust our behavior if we want to feel safe and be treated like people. Don’t wear the short skirt. Don’t drink at the party. Don’t walk at night. Don’t walk alone. Don’t turn him down; he could turn violent. Leave your job. Find a new job where you are not harassed.

Al Franken, Aziz Ansari, and now Morgan Freeman are harder to grapple with than cut-and-dry predators like Harvey Weinstein, because we tend to think of them as comparatively not that bad. One of Freeman’s accusers testified that he “kept trying to lift up my skirt and asking if I was wearing underwear.” If you’re a woman, maybe you remember the time a classmate dropped a pencil at your feet so that he could look up your dress, or the time your creepy uncle got disturbingly fresh. If you’re a man, maybe you remember carrying out some of this behavior yourself, justifying that it was all in good fun.

Every time a Morgan Freeman is exposed, a swath of internet commenters throws their hands in the air. “Well,” they ask, “What should be done? Should we stop watching his films? Should he be fired? Do we take him out to pasture? ” These kinds of questions are understandable, especially considering that our society privileges a masculine ethic of justice. But I don’t think that they are the most important questions. My co-worker left a previous engineering position she loved because, as the only Hispanic woman in a group of white men, the harassment she endured was unmanageable. For every one of her, there are a thousand more women with a similar story. I am more interested in the consequences that these women face as a result of serial harassment and abuse: coming forward to someone who either buries their allegations or makes the climate worse, suppressing feelings of shame, embarrassment, and lack of professionalism, staying at their jobs and being miserable, or alternatively leaving.

Forgive me if I care much less about the fate of one serial creeper’s career than the scores of women who have to compromise theirs.

Do the allegations against Freeman suggest rape or assault? Certainly not. His misconduct doesn’t warrant a punishment of being carted off in handcuffs (bye, Harvey!), but it does call for some serious introspection. I’ve noticed that when angry commenters online moan that #MeToo has “gone too far,” it is usually because they are no longer able to distance themselves from the perpetrator in question. Harvey Weinstein was a living nightmare to work with, easy to dismiss as a “monster” with no moral compass. Aziz Ansari was harder. His conduct refused categorization, and I watched as even self-proclaimed progressive, feminist men struggled to bend the story into something excusable. They resented the emotional labor that came with knowing about Aziz Ansari, about Morgan Freeman, because it could lead them to potentially upsetting places. Of course, women are no strangers to emotional labor, which is necessitated by everything from managing a home to smiling on the street to placate strangers. This labor is a reflex. We don’t think twice about adapting to situations, managing expectations, or evaluating what we could have done differently. One of the biggest challenges for #MeToo, I believe, is to encourage a similar self-reflection among men.

In this way, I want #MeToo to act as a mirror. For men all over the country, all over the world, to listen to not only what women experience, but to how women constantly adapt their daily lives to avoid getting groped or followed or belittled. And then I want men to reflexively adjust, to turn inward and evaluate their own past and present conduct. Confront things that have been normalized, but that are actually not OK. Confront times when they may have treated women as less than human. Even if it’s uncomfortable. Especially if it’s uncomfortable. Our safety and livelihood depend on it.

Chelsea Cristene is a communications associate and English professor based in Washington, DC. She has been published by the Good Men Project, Salon, xoJane, and MamaMia, and runs a film review blog, Catch Up, with fellow Role Reboot contributor Telaina Eriksen. Find her on Twitter.

Other Links: