At a time when so many of us, including me, are often reduced to screaming instead of listening, to fighting instead of loving, we need Fred Rogers’ example more than ever.

In Morgan Neville’s astonishing documentary, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, Fred Rogers, the host of the long-running children’s program Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, testifies before the Senate Subcommittee on Communication, asking for $20 million to fund public television. Facing down chairman Senator John O. Pastore, a budgetary hard-liner, Rogers eschews any quantifiable justification for the money. Instead, he argues that his show is an attempt to help young children deal with complex problems, thereby enhancing youngsters’ mental health and self-esteem. He illustrates his methodology by sharing the lyrics to one of his show’s songs.

Incredibly, a visibly moved Pastore agrees to provide the $20 million. If you are reading this in 2018, mired as we are in a political tarpit; if you are my age (47) or younger; if you have grown weary of and cynical about the political posturing from both the Democratic and Republican parties; if you wish that Americans had more than two options, and that our leaders would work together, and that citizens and politicians alike would listen to each other with empathy and open minds, then this scene alone is worth the price of admission. It is a moment of connection and hope wherein personal and political agendas and avarice are set aside so that children might enjoy better lives.

In 2018, can we even imagine such a scenario? Would we believe it ever happened if we weren’t there, or if films like Neville’s didn’t provide video evidence that the words “Washington” and “conscience” don’t have to be mutually exclusive?

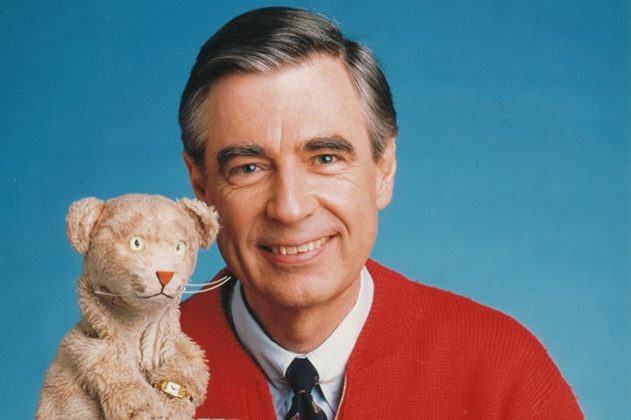

As an active child with good friends and a strong desire to play outside, I was not a devotee of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. When I stayed indoors and stumbled on an episode, however, I watched it passionately. I did not possess the vocabulary to say so, but I recognized the low yet charming production values, Rogers’ surreal aura of happiness and calm, the somewhat didactic yet earnest and honest lessons he taught. It is hard to imagine a man like Rogers or a show like that in 2018. We have become too cynical and ironic.

In fact, until watching Won’t You Be My Neighbor, I had forgotten how forthright and raw the show could be, breaching such taboo-in-front-of-the-kids subjects as racism and assassinations and political tyranny. Can you imagine Dora the Explorer or Bubble Guppies exploring a storyline about authoritarianism? How would Donald Trump respond on Twitter?

Perhaps equally surprising to contemporary audiences, Rogers was a lifelong Republican. He testified before Pastore in 1969, several years after Barry Goldwater’s disastrous presidential run jumpstarted, in some ways, the modern reactionary movement, including far-right Republicans’ ties to evangelical Christianity and their opposition to civil rights. Rogers himself was not immune to the sociopolitical prejudices of his time; another striking part of the documentary details his forcing François Clemmons (“Officer Clemmons”) to choose between publicly attending gay clubs and working on the show.

Perhaps Rogers’ time studying to be a pastor and conservative Christianity’s generally backwards view of human sexuality influenced that moment, an outlier in a life filled with love and acceptance. In contrast with his behind-the-scenes disapproval of Clemmons’ sexuality, the film reminds us that, at a time when African-Americans were unwelcome in most “white” public swimming pools, Rogers shared a foot-bath in a plastic kiddie pool with Clemmons, a symbolic rebuke to racist America. For most of the 1970s and ’80s, my hometown’s public pool existed in an unspoken “whites only” pocket universe in which desegregation never happened. I vividly remember my own surprise the first time I saw black kids in the pool. In the deep south, de facto segregation still existed in post-legal-segregation America. It took African-American kids’ presence in the pool for me to realize they had always been absent—white privilege in action.

How did Fred Rogers reconcile his deep Christian beliefs and, for the time, progressive politics with his political affiliations? How did he explain any contradictions to his cast, his family, his friends? Won’t You Be My Neighbor doesn’t show us. Instead, it reveals that the cast, the crew, his family, his friends, his acquaintances, and children of all genders, races, abilities, and creeds universally loved the man. For his part, Rogers spent his life ministering to children—not proselytizing an evangelical Christianity that Jesus himself would not recognize, but providing a sterling example of loving our neighbors, understanding life’s disappointments and travesties, and letting the ideals of empathy and peace carry us through the bad times.

Perhaps the question above about whether our cynical, ironic age would find room for Fred Rogers is answered when the film addresses conservative news outlets’ blaming him for what they characterize as a trend toward self-love and entitlement. On his show, Rogers tells us that we’re all OK just the way we are and that we don’t have to do anything specific to be special. Taken to its farthest logical conclusion, perhaps those news outlets’ point isn’t completely wrong, but it does misinterpret what Rogers meant—that you don’t have to be white, or male, or Christian, or abled, or rich, or straight to be loved; that diversity is not only acceptable but treasured; that all individuals carry the potential for greatness.

*****

Won’t You Be My Neighbor begins with an interview wherein Rogers discusses his philosophy. He says, “Love is at the root of everything—all learning, all parenting, all relationships. Love or the lack of it. And what we see and hear on the screen is part of who we become.”

It is hard to imagine a more succinct, powerful call for connection, or a stronger statement for why art and popular culture remain so crucial to the human experience.

At a time when so many of us, including me, are often reduced to screaming instead of listening, to fighting instead of loving, we need Fred Rogers’ example more than ever. He died in 2003, but his work and his ministry remain. Watching Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and, by extension, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, can be akin to a religious experience, more so than attending many actual churches. In that light, it is little wonder that the animated version of Daniel Tiger—a puppet stand-in for Rogers, according to the film—now seems almost messianic to young children like my granddaughter, my niece and nephew, and my friends’ children. We all yearn for someone calm, rational, and loving who will tell us that, no matter how dark the world seems, we’ll all be OK.

Won’t You Be My Neighbor? reminds us that our “someone” doesn’t have to be a literal messiah or a President. Sometimes it can be the smiling, singing person next door.

Brett Riley is the Pushcart-nominated author of The Subtle Dance of Impulse and Light (Ink Brush Press) and the feature-length screenplay Candy’s First Kiss, which won or placed in five contests. His short fiction has appeared in journals such as Solstice, Folio, The Wisconsin Review, Red Rock Review, The Evansville Review, and many others. Email him at officialbrettriley@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter and Instagram: @brettwrites.

Other Links: