Rather than tell a single woman to change, we need to keep focused on the entire system.

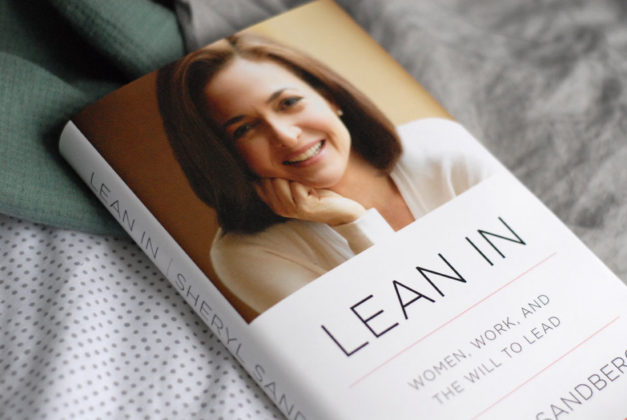

This year marked five years since the publication of Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead. It quickly became part of the zeitgeist, an offhand reference to the work women must do to succeed in a corporate space. So it came as no surprise that, during her book tour, First Lady Michelle Obama referenced the book on stage as she discussed marriage and work. “Marriage still ain’t equal, y’all. It ain’t equal. I tell women that whole ‘you can have it all’ — mmm, nope, not at the same time, that’s a lie. It’s not always enough to lean in because that shit doesn’t work.” For a treatise on work to lead to commentary on inequality in (heterosexual) marriage reflects the continuing cultural importance of Lean In, as well as its shortcomings and controversies.

While Sandberg would likely resist this description, Lean In is best described as a self-help book. In it, Sandberg argues that women should be unapologetically ambitious about getting to the top of their field. She suggests that at such heights, women can make change for other women – as in her example when, as a pregnant woman, she asked for a parking space designated for pregnant women. For Sandberg, while structural barriers against women exist, fear is the biggest obstacle of them all. In addition to external societal barriers, women hinder themselves — we’re not as ambitious, we take ourselves out of the workforce, we lack self-confidence, and have low self-expectations. Thus, Sandberg wrote the “How-to” for dealing with the hurdles we can control and make it to the top. It is a kind of trickle-down feminism text, promoting the idea that more women on top will help other women on bottom.

In this way, it fits easily alongside a culture that prefers diversity programs over affirmative action. It is much easier to promote the notion that different people offer beneficial perspectives and backgrounds for everyone than to contend with all the reasons they are excluded in the first place. Such approaches to dealing with structural discrimination tend to gloss over and deemphasize institutional bias. Thus, Sandberg celebrates the United States as “centuries ahead” of women in countries like the Sudan and Afghanistan, and conveniently forgets wage disparities, anti-reproductive health measures, and rates of domestic and sexual violence in the U.S. She praises the suffragettes who “marched for equality” for women’s enfranchisement while forgetting that many of them wielded racism to push against the vote for black women.

But beyond what is best described as “white feminism,” Michelle Obama aimed her critique about marriage inequality at a key weakness of the book – in what way is it an aspirational text rather than one rooted in reality? For women who are not Sandberg – that is, white millionaires in heterosexual marriages with children, lots of paid domestic help, and flexible work — to what extent can a book that excludes a focus on structural obstacles be helpful? While Sandberg seems to be advancing the idea that women can have it all if they work hard enough, women like Michelle Obama remind us of all the reasons they cannot.

For Michelle Obama, her husband’s own career ambition has been an obstacle. In her relationship, taking care of their children and home fell largely to her. In Barack’s biography he writes that she would tell him, “You only think of yourself…I never thought I’d have to raise a family alone.” In an interview she said, “What I notice about men, all men, is that their order is me, my family, God is in there somewhere, but me is first….And for women, me is fourth, and that’s not healthy.”

In truth, Sandberg’s text is a reflection of our current struggles in feminism, where individual success is conflated with a collective win. Her book is an ode to neoliberalism, a political philosophy that believes in private, individualized market-based solutions to public problems or issues. Sandberg avoids structural demands or recommendations that can help promote women’s equality because it’s safer for her and her own position in the corporate world to push the onus on women themselves. Sandberg is committed to projecting the notion of a benevolent corporation, mirroring the brand image of her own employer, Facebook. It’s a shiny veneer that betrays the reality that businesses prioritize profits over people. And it pretends that Sandberg’s influence is limited to her own business rather than the politicians and officials who can regulate better pay, family leave, hours, and workplaces for everyone. Rather than tell a single woman to change, we need to keep focused on the entire system.

Ultimately, there are some things to like about Lean In five years later. It came at a time when women were really hungry to hear about what they could do to fulfill their goals and it provided that advice. It helped women have a conversation that centered them and their goals beyond families and romantic relationships. It told women not to take themselves out of the running for opportunities. But it also drew on the false comfort of believing that America is a meritocracy and that we can get what we want if we work hard enough. Five years later, Lean In is more useful as a way to think beyond ourselves and ask what we want for all women. And hopefully that’s a conversation we’ll continue to have.

Khadijah White is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Journalism and Media Studies at Rutgers University. She is currently writing a book on the rise of the Tea Party brand in news.

Other Links: