She reminds me to breathe and feel the weight of my own body, to cement my space in the universe. Her words are a means of recalibrating. Her poems are restorative.

Someone I loved once gave me

a box full of darkness.

It took me years to understand

that this, too, was a gift. – Mary Oliver, “The Uses of Sorrow”

Is this a box of darkness? This country, at this moment, governed by an administration that tears children from the arms of their mothers. Even the most beautiful literature is hard to swallow these days, depending on how dark it is. “I had trouble with this book,” my professor admitted last fall, crossing her hands over Shelley Jackson’s Riddance. “There’s no kindness in it. Right now, I need kindness.”

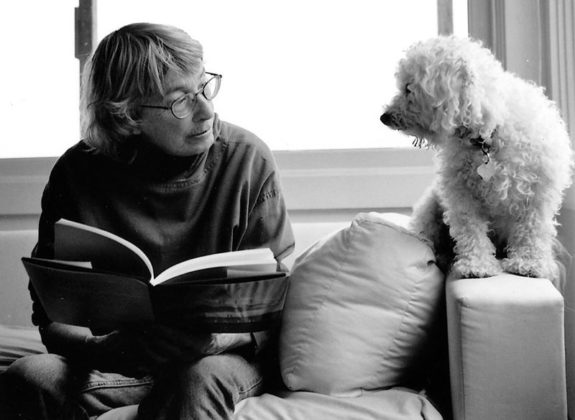

Several years ago, a different professor and now mentor and friend gave me a recently published collection from one of her favorite poets, Mary Oliver. “To borrow?” I asked. “To keep,” she said. “To keep close and to fill you with gratitude.” The collection is called Why I Wake Early. It remains one of my nightstand books, crammed with strips of paper to mark the poems I need, when I need them.

Why do I wake early? Truth be told, I usually don’t. Sleeping is one of my dearest hobbies. But when I do wake, no matter the time, Mary Oliver is always there to set the attitude of the day. She grounds me to warm stones and peony buds, to the world that has in it nothing fancy. She reminds me to breathe and feel the weight of my own body, to cement my space in the universe. Her words are a means of recalibrating. Her poems are restorative.

The universal appeal of Mary Oliver’s work is one of the many reasons that I hold her so close to my heart. No matter how often my literature syllabus changed from semester to semester, her poem “Wild Geese” remained a fixture. It was always the last poem in our poetry unit, and the one that most students chose to write about for their papers. You do not have to be good, the poem opens. You do not have to walk on your knees / for a hundred miles through the desert repenting / You only have to let the soft animal of your body / love what it loves.

As English teachers, we use poetry as a vehicle for other lessons. Jesse Pope and Wilfred Owen illustrate wartime tensions; Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsburg introduce the anti-consumerist counterculture of the 60s. Mary Oliver does something else. One by one, as I played a video of her clean voice reading “Wild Geese,” my students softened in their chairs. You do not have to be good. The poem gave them permission, amid their hectic schedules and responsibilities, to be imperfect. It gave us all permission to be soft animals: humble, kind, awake to the beauty of the world.

But after Mary Oliver’s death last week, we must realize that a person lived beneath the joy that she brought her readers. She was a spiritual guide who found God in every mountain and stream. Long before that, she was a frightened child sexually abused by her father, who often coped by vanishing into the woods with a volume of Walt Whitman’s poetry and a notepad. An intensely private person, Mary Oliver eventually opened up about her past to Maria Shriver. “I had a very dysfunctional family, and a very hard childhood,” she explained. “So I made a world out of words. And it was my salvation.” Mary Oliver, like so many of us, learned to assuage her pain by creating beauty in its place. She is a bastion of hope in a country where sexual predators are excused and their victims are punished. Her poetry is revered for its simplicity, but it also comes from a place of deep resistance. Mary Oliver wrote to survive, which is perhaps why so many of us read it to survive.

Mary Oliver was also a queer woman who lived with her partner, Molly Cook, for over 40 years until Molly’s death in 2005. This matters, especially during a time when many of our leaders are using Christianity to sanction hate. Since Donald Trump’s inauguration in 2017, his administration has attempted to reinstate a ban on transgender Americans in the military, nominated anti-LGBT judges, and excused anti-LGBT business practices under the guise of “religious freedom.” Within this context, we cannot forget that Mary Oliver lived and died as an openly queer believer in a higher power. Her legacy is teaching us to look and see rather than manipulating God to achieve hateful ends. Oh Lord, how shining and festive is your gift to us, she writes, if we only look and see.

Mary Oliver was a gift to us. We are lucky to have had her on this earth for 83 years, sharing her light with us, no matter how troubling the darkness.

Chelsea Cristene is an international student adviser, English professor, and graduate student based in Washington, D.C. She has been published by the Good Men Project, Salon, xoJane, The Establishment, and MamaMia, and has appeared on HuffPost Live. Find her on Twitter.

Other Links: