Mom: I realize now, that in order for me to see and know myself, I need to be able to see and know you.

My aging father had finally put his foot down last April: “You need to get over here and clean out this attic.” Sitting there in the sweltering desert heat rifling through dusty boxes and plastic tubs, I discovered neatly-organized, chronologically stacked shoe boxes full of letters my deceased mother had written and received over her lifetime. Here were letters she’d written to her parents who lived thousands of miles away, letters to my father while they were courting and he was in residency, and even glossy seasonal postcards from her favorite football team The San Diego Chargers.

I felt a secret thrill in discovering these boxes, as well as a bittersweet longing for her. I was taking such a deep look into a private part of her life that I never had access to while she was alive. What mysteries were hidden in these letters? What would I find that had, until now, been carefully tucked away in the attic?

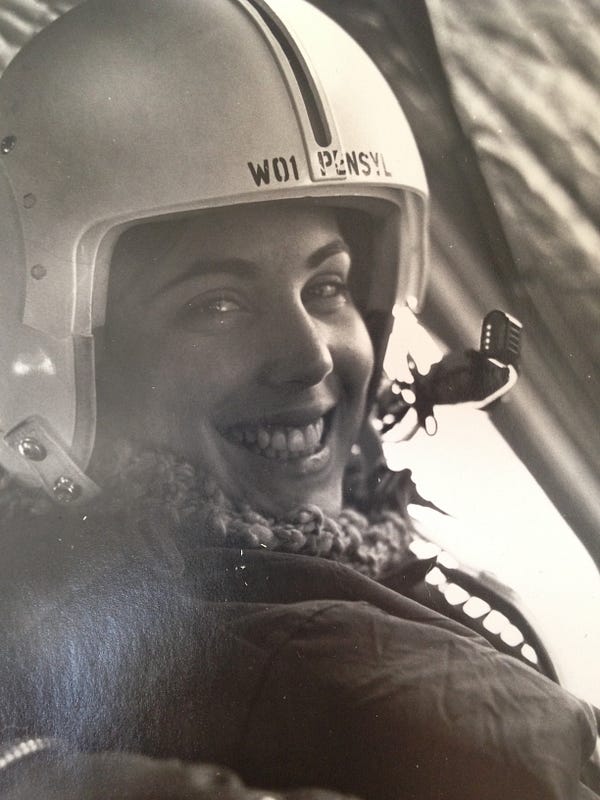

I discovered my mom was a helicopter pilot in her spare time.

As I dug through boxes full of various cards, letters, and photographs, I started to understand the difference between this kind of correspondence and the kind I’ve become accustomed to over the last decade. I had never emailed my mother — she died in 1997, before email was really a thing. It seems like it’s possible for email to function in much the same way as a handwritten letter, but it lacks the messy, tactile, human element that paper letters can provide.

In writing a letter, you put a piece of yourself on paper, informed by your fantasies of the world that exists between yourself and the recipient. And when you read a letter, you see the soul of the writer through the artistry of the words. You see the writer’s mood change as the mood of the letters change: Short, choppy handwriting, loose and floppy lettering, squeezing a too-long word into a too-short space. You can trace the writer’s thought pattern through the scratch-out marks, boldly black as if to say, “Here lies something that I am ambivalent about you knowing: a thought that I no longer believe but that I need you to see.”

The paper has a smell, a texture, and maybe even some of the writer’s DNA if they licked the glue on the envelope. You simultaneously know, and don’t know, in writing the letter, whether all of these intimate, tactile elements will come through if the recipient looks hard enough. Then, you send it off on a stamp and the wings of faith that it will reach its destination.

Since email programs save a copy in the “sent” folder, you can look back on it and regret the way you phrased something for as long as you want. But with paper letters, they’re gone.

Even to this day, I’m perplexed: How did my mom’s correspondence stay with her all this time?

Had she sent these letters and then retrieved them when her own parents died and after her divorce from my father? Had she kept secondary handwritten copies, wanting proof of her life narrative? Or had she never sent them at all, too frightened by the inevitable vulnerability of sharing her heart on paper?

She would often tell me something her dad used to say: “Never write anything down that you wouldn’t want published on the front page of the newspaper.” But, as evidenced by the mountains of shoe boxes in the attic, she wrote anyway.

The letters I found talked about her life, about her wishes for her future, about her daily musings at home. She also wrote about her fantasies of my brother and me before we were conceived.

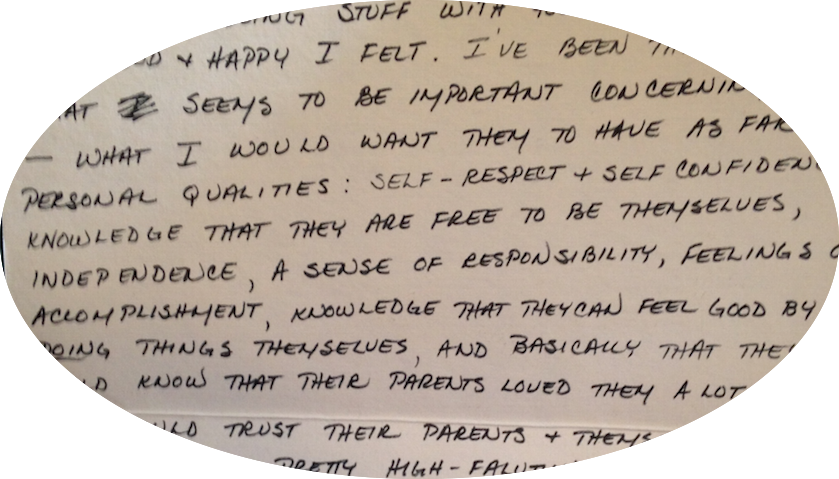

“I’ve been thinking about what seems important concerning children—what I would want them to have as far as personal qualities: Self-respect + self confidence, knowledge that they are free to be themselves, independence, a sense of responsibility, feelings of accomplishment, knowledge that they can feel good by doing things themselves, and basically that they would know their parents loved them a lot + they could trust their parents + themselves.”

Written in her signature all-caps style, this letter tells me she wanted us to grow up strong, capable, and unconditionally loved. I was moved by this vision of a future with my father and of who my brother and I, as yet not biologically conceived, would grow up to become. Her relationship with my dad, and mine and my brother’s with hers, were all sparked there in that letter, before she could possibly know what her words would come to mean.

Elements of identity and relationship are formed when people hold each other deeply in mind during those times when they cannot actually see each other.

After reading her letters, I had a dream about my mother. I was looking at her face, and I could see that she was human and preoccupied by human matters. She was someone who wrote letters to people who were important to her, people who were important to her idea of herself. Maybe she wrote so she could see herself, starkly on card stock, to ponder who she was becoming by writing about who she was. We all project parts of ourselves onto the people in our lives. That’s how we get to see who we really are.

Mom: I realize now, that in order for me to see and know myself, I need to be able to see and know you.

We need to keep our communication lines open—and not just through our words. And I am starting to understand that the more willing I am to be found, the better I can be connected to the people I love.

Though I still don’t understand exactly why or how she held on to those letters, I am glad that they were saved for my brother and me to read. I’m not sure, now, whether email could have the same significance for the next generation. What are we preserving, and what do we keep? We often can’t be sure today what will be valuable in 20 years — that’s for our children to decide.

I’m lucky that these letters were kept so that we could know our mother, two decades after her death, in ways she could never express to us. She understood, somehow, the importance of writing letters and of holding on to them. So that she, and later we, could be found.

Molly Merson, MFT is a psychotherapist in Berkeley, CA, who dedicates her work to helping people explore beneath the surface to know themselves deeply. She also runs small, intimate groups on practicing self-care. When she is not being a therapist, she is writing, reading, hiking with her dog, and lifting heavy weights.

This originally appeared on Medium. Republished here with author’s permission.

Related Links: