Understanding the significance of my father’s childhood has helped me understand my father, and untangle our complicated relationship.

My father is the child of Holocaust survivors. It’s strange for me to type those words because that was never how my father described his parents.

His parents never discussed the Holocaust or the war.

When he looks back on his childhood, my father remembers more fighting than talking. He remembers his mother making chicken soup every night for his father, a gesture of consolation after their day of bickering.

He remembers his father’s callused hands. His father, up at 5am, delivering milk to all the families in the neighborhood. Always exhausted from walking up and down the humid hills of Haifa, Israel. Never time to talk with his children.

There was a veil of misery over his house, a dense fog.

My father was the “bad” son; a shy, sensitive child who didn’t speak for all of kindergarten; an emotional, distracted teenager who couldn’t concentrate on school work and spent his days lying in bed, listening to Beatles records and staring up at the ceiling.

He felt the brunt of his parents’ anger—an anger that drove my father out of the house at 18, and out of the country with his American wife (my mother) at 24. He barely spoke to his parents for the rest of their lives.

It is unclear whether either of his parents was in a concentration camp—they never told him, and he never asked. What is clear is that their former lives disappeared into thin air during the war, and that the life they led as my father’s parents was essentially a second, invented life.

The things I know about them during the war are scarce, little snapshots.

Snapshot 1: My grandfather had a previous wife and a daughter, both killed in concentration camps. He fled from Poland to Israel, with a pit-stop in Greece, hiding out along the way. The hope was that he could send for his wife and daughter when the time came. It never did.

Snapshot 2: My grandmother came from a large family in Poland. She lost everyone in the Holocaust—parents, brothers, sisters, uncles, and aunts. When my grandmother saw me at 14 years old, she held back tears. I looked just like her sister Miriam.

And that is all I know.

But I know something about trauma. Traumas which are not explored, talked through, screamed through, whatever it is—do not go away. They live in the subconscious, in clenched teeth, in angry fists on the dinner table. They are passed from mother to child, from father to child, down through each generation. They are morphed into anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders.

There is some fascinating research specifically about descendents of Holocaust survivors. Researchers have detected epigenetic changes in the children of survivors—specifically, lower than average levels of the hormone cortisol, the hormone necessary to bounce back after trauma. Children of survivors are more prone to PTSD, and other anxiety disorders.

Indeed, my father has often suffered from anxiety, as have I. Only now, in my late 30s, have I been “coming out” as a sufferer, and trying to understand its origins.

I believe the roots of my anxiety are a complex mix of nature and nurture. But the story of my father’s parents is one of the most illuminating parts because I have always felt that my body reacts to stress quite differently than other people.

I have always been labeled “sensitive.” As a baby, I had colic; I cried from 3pm till midnight. I was sensitive to loud noises. I was shy. Since I was a teen, I have had periods of severe panic attacks. I can feel a stranger’s angst from across the room. A baby’s cries are like daggers to my heart.

I have learned to adapt. I have learned to say no to the things that trigger me (crowded places, scary movies, parties), and yes to the things that center me (yoga, meditation, small gatherings).

Perhaps most importantly, understanding the significance of my father’s childhood has helped me understand my father, and untangle our complicated relationship.

He and I were very close in my early childhood. Our temperaments are similar: We are both passionate, quiet, creative. I have wonderful memories of listening to music with him, going on adventures in the woods, and just generally clicking with him. His love for me was fierce, tender, enveloping.

That is why it stung so much when I was 5 and he left my mother. He continued to be involved in my life, but his role was more peripheral. I felt his absence deeply; I longed for things to be the way they were when I was little.

When I was 12, my mother moved us across the country from my father to live near her parents. There was an anger unleashed in my father then that devastated me. But I see now that part of this had to do with how he was wired to respond to stress, and that he must have felt as abandoned by me as I had by him.

My father is easily wounded. He holds the traumas of his own parents in his heart and body. What might be little heartbreaks for some have felt to him like earthquakes. That is who he is: I see it now. When I was younger, I just felt his abandonment, his anger—and it crushed me. Now I understand him a little better. I accept him.

But I wish I could take it back, all of it. I wish I could rescue my grandfather’s wife and child. I wish I could reunite my grandmother with her brothers and sisters. I wish I could return my father to me. I wish I could return myself to my father. And I wish I could rewire our bodies, erase the markers on our DNA, grow us each a thicker skin.

But I can’t do any of that. All I can do is learn about the past, and let it go. All I can do is heal, rebuild, strengthen, and adapt. And most of all—forgive.

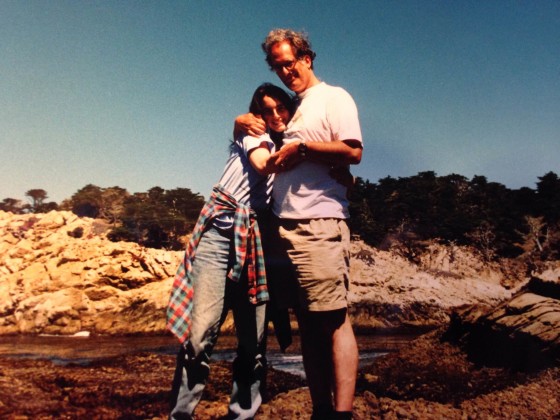

Photo of the author and her father

Wendy Wisner is a mom, writer, and lactation consultant (IBCLC). She is the author of two books of poems (CW Books), and her writing has appeared in such publications as The Washington Post, Huffington Post, Brain, Child Magazine, Scary Mommy, and Mamalode. She lives in New York with her husband and two sons. Find Wendy at WendyWisner.com. Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Related Links: