We are scared to face women who have gone through a pregnancy loss or the loss of a baby and we don’t know what the hell to say—even if we’ve gone through it ourselves.

I had a miscarriage.

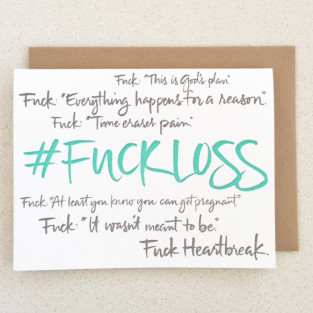

It’s not something I’ve written about before. But last week’s launch of Dr. Jessica Zucker’s “pregnancy loss cards” for women who have experienced pregnancy or baby loss ignited in me the desire to understand more about my own emotional response to my miscarriage over the last 15 years and how we, as a culture, don’t seem to have the right words to share with women who have gone through a miscarriage or stillbirth.

Millions of women have traversed these mountains and it’s past time we acknowledge how hard they can be to climb. Approximately 15-20% of known pregnancies result in miscarriage and there are almost 260,000 stillbirths every year in this country. (When a pregnancy is lost before 20 weeks, it’s a miscarriage. After that, it’s considered a stillbirth.)

Yet women and those who love us often remain paralyzed or unsure of just what we’re supposed to feel or say when it comes to the loss of a pregnancy or a baby.

For me, it happened when our first child—our son—was 18 months old.

At the time, I treated the miscarriage as if it was no big deal and over the years when I’ve thought back, I’m always surprised that I didn’t feel more during and immediately following.

I didn’t talk about it much when it happened. Women are taught not to talk about our difficult reproductive experiences whether it’s birth, abortion, miscarriage, stillbirth, or any number of reproductive health related issues. And if we do, our emotional responses are highly regulated by society. Our stories of life growing inside us, or of the ending of that life whether by choice or chance, either during pregnancy or during birth, often remain secrets, and when shared, tend to be used as fodder for political, religious, and cultural debate.

So I didn’t know that many others in my life had miscarriages or stillbirths let alone experienced a range of emotions related to them.

*****

From the beginning, this pregnancy seemed different than my first. I wasn’t nearly as excited or sure of myself. I felt at turns nauseated and numb. I also felt unnervingly unattached to the life growing inside. Emotionally and physically. It was as if this being was growing alongside and not inside me. I chalked it up to my initial anxiety with the pregnancy and my and my husband’s worry about having a second child, unexpected and without our feet firm.

The pregnancy progressed and, at our eight-week appointment with the nurse midwife who cared for me before and during my son’s birth, we heard the heartbeat for the first time. I felt the flutter of connection and decided it would take time to grow into full-fledged love. At our 11-week appointment, I lay down on the exam table, with my husband David standing at my side holding my hand. The midwife rolled the ultrasound around my slick abdomen, ready to belt out the beating of our baby’s heart. Eleven weeks is when the embryo officially becomes a fetus: another reason, I compelled myself, to build a bond with my growing baby.

Only this time our midwife couldn’t find the heartbeat. She tried. The seconds toiled into minutes. Her long, gray hair draped her face as she slid the small tool around, searching. David’s hand gripped mine tighter. Teary-eyed, after confirmation in another room with a doctor, our midwife gently told us that the (female) fetus was dead and quietly left the room to let the reality sink in. We were shocked, crying, confused.

It never occurred to me that my body might not sustain the one growing inside me. I failed, I thought. I failed to keep the life dependent upon me healthy, to grow and change and evolve and become. It was my fault. I didn’t want this baby badly enough and I let it die, wither away, under the weight of my ambivalence. I had no idea how to talk about that, let alone what to think about my feelings. I stayed in that place for many years to come.

*****

When I interviewed Dr. Zucker about her cards, it became clear to me how desperately our culture needed to talk about loss. And how fervently women are taught to disregard the pain and grief we might experience from pregnancy loss. There is universality in grief, of course. But there is also a fear that, as Dr. Zucker told me, “Talking about loss will induce loss” and that “miscarriage or grief…is contagious.”

In other words, we are scared to face women who have gone through a pregnancy loss or the loss of a baby and we don’t know what the hell to say—even if we’ve gone through it ourselves. Some women, says Zucker, “compare and contrast” the depth of our tragedy and minimize our own feelings:

“After my miscarriage at 16 weeks, I had a lot of people say to me: ‘your miscarriage is so much worse than mine. Mine was easy, because it was only at six weeks (or eight weeks). It was no big deal compared to what you went through.’ Why would we do that? We’re going to compare our losses? That is not healthy for any of us.”

Zucker sees the cards as tools not only for the receiver, but the giver as well: “These cards say I’m empathizing with you and the feelings you might be having.” In that way, women slowly begin the process of cracking open the shells that seem to harden over years, hiding our feelings about our own loss, and forge a path between the truth and validity of our experiences and those of other women in our lives.

When women share stories with each other, we find better, more helpful, and more supportive ways to talk about what we’re feeling and going through. But we also confront the reasons behind our silence. When I started writing this essay, I found myself writing about my miscarriage story until I had recorded the whole timeline. I unearthed sadness, anger, and even some humor where I thought I had none of these. These were emotions I never let myself feel about the loss of my second pregnancy because I didn’t know how. Because no one in my life, through no fault of their own, had the words either. Because society taught me not to speak my truth about the loss of my pregnancy.

After my miscarriage, well-meaning people told me: “It’s OK. You’ll get pregnant again.” “Maybe this is a good thing because you were unsure about whether you wanted the baby anyway.” “There was clearly something wrong with the baby. It’s better that this happened.”

It wasn’t that people were intentionally uncaring or thoughtless. They just didn’t know how to talk about it.

As Dr. Zucker wrote almost one year ago of her own miscarriage experience, in her New York Times Motherlode post that helped the hashtag #IHadAMiscarriage go viral:

“We shouldn’t feel ashamed of our traumas, nor should we hide the consequent grief. It’s not that I necessarily feel proud of having a miscarriage, but I do feel compelled to question why it seems as if we rarely talk about pregnancy loss, though the statistics are staggering. Is it resounding cultural shame? Speckles of self-blame? Steadfast stigma? The notion that talking about ‘unpleasant’ things is a no-no? It’s a hard topic. But if every woman who has lost a pregnancy to miscarriage or stillbirth told her story, we might at least feel less alone.”

Dr. Zucker says she wants the cards to be used to help start conversations about pregnancy and baby loss; not only as “greeting cards.” These cards are meant to give voice and words and meaning to women’s experiences and emotions after the loss of a pregnancy or a baby:

“Do I intend to become a greeting card maker? No. But what I envision is that they offer cultural messages around how to talk about these experiences. The way I envision these cards being used is not only for one person to give to another but that, in this world of social media, they get shared, pinned, maybe someone sends it to someone else and says, ‘This is what I meant to say to you! I may have put my foot in my mouth! But this is what I truly wanted to say!’

Here’s what it comes down to for me: Women have a right to talk about these experiences, even (and sometimes especially) if it makes people feel sad or uncomfortable to hear. Once we talk about our losses—the sticky mess of miscarriage or the gut-scrapping sadness that comes from losing a baby from a stillbirth—we honor our stories, our bodies, our feelings. We take power away from those who seek to write our stories for us and we face our fears. We strengthen the bonds between our shared experiences.

Though I had never written my whole miscarriage story before, over the years I’ve opened up with friends and family. I am shocked at how many women have revealed their stories to me. Greeting cards aren’t going to wipe away our feelings and make dealing with our own or a loved ones’ pregnancy or baby loss easy, of course. But I would have loved a “Fuck: It wasn’t meant to be’” message after my miscarriage, or included in my support for a friend who experienced the loss of a baby, “I imagine you feel like shit right now but I just had to remind you how wonderful I think you are.”

Resources:

What to Read About Grief, Miscarriage, Stillbirth, Heartbreaking Decisions, and Parenting After Loss

Amie Newman is a global women’s health communicator, a procrastinating writer, and a recovering good, white person who lives in Seattle with her partner and their two beautiful teen-humans.

Related Links: