What I hope for my daughters—for young women everywhere— is an authentic experience of sexuality, free from self-consciousness, shame, or violation.

When Ariana Grande and Miley Cyrus sang together at One Love Manchester, an all-star benefit for victims of the May 22 terrorist attack, they showed tenderness instead of hotness, a shift from their usual pop personae. Both young women have been denounced for their brazen sexuality, and both have unapologetically refused to tone it down. At the concert they looked almost like sisters, holding hands in baggy shirts, belting out Crowded House for 50,000 fans. It was an emotional performance, both vulnerable and authentic, a triumph of courage over fear. Watching them, I felt proud that Ariana was my 11-year-old daughter’s favorite recording artist, and sorry that I’d been a hater.

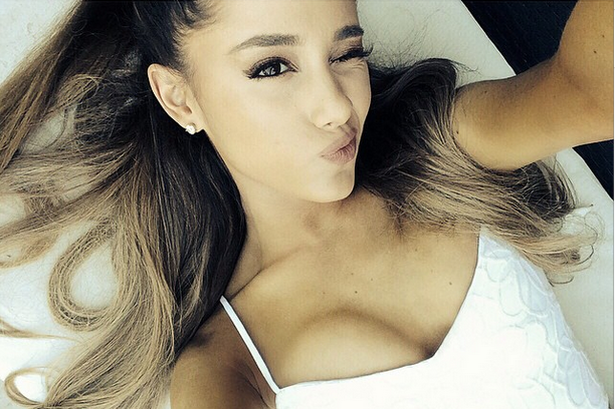

Before Manchester, I discounted Ariana as yet another pop princess in the child-TV-star lineage. I saw the ponytail, the lashes, the lingerie, and didn’t look any further. Then came the horrific bombing and Ariana’s compassionate response. After I read Amanda Petrusich’s commentary in The New Yorker, I realized I’d misjudged a potential role model:

“Many of Grande’s songs are about self-actualization, and the unashamed consummation of certain lustful desires. For young women, especially, learning how to celebrate (and not fear) these sorts of feelings can be challenging. Grande often sings of weighing (and then indulging) what her body wants: the odd delight of letting pleasure subsume you. Girls are rarely taught to think this way; watching a figure near their own age oblige and accommodate her hungers can be profound.”

So this was the music my sixth-grader was enjoying behind closed doors! “I know all the lyrics of every song on Dangerous Woman,” she’d told her little sister, reciting the title ballad upon request: “Don’t need permission/ Made my decision to test my limits…” My girl may not grasp the full sexual connotations yet, but she can hear the power of a young woman taking charge of her own life.

Ariana’s fans—including 109 million Instagram followers— are largely tween and teenage girls. It’s likely that the Islamic State’s terrorism in Manchester was targeted at young women; Slate called the attack “a massive act of gender-based violence.” Since her ascendance, Ariana has used her megastar platform to spread messages of female empowerment, quoting Gloria Steinem and continually asserting her autonomy: “I am tired of living in a world where women are mostly referred to as a man’s past, present, or future property/possession,” she tweeted in 2015. Last December, in response to critics who called her overly sexual, Ariana declared a woman’s right to dress, dance and act however she liked: “expressing sexuality in art is not an invitation for disrespect!!! just like wearing a short skirt is not asking for assault.”

I applaud the star for raising awareness about sexual assault on social media and in person, though I sometimes question her methods. During an interlude in her Dangerous Woman tour (which now continues in Europe) a huge video screen plays images of Ariana’s face and body. Words flash in all-caps as the singer, in full-on siren mode, poses in a white bodysuit and legwarmers, arching her back, tossing her hair, gazing at the camera: “EMPOWERED… STRONG… GROUNDED… CENTERED… CONNECTED… NOT ASKING FOR IT…” Her chosen adjectives celebrate the contradictory aspects of femininity— SOFT/HARD, LADYLIKE/WILD— while the refrain “NOT ASKING FOR IT” repeats.

All hail to any pop icon who takes a public stand against rape culture, but something troubles me about the interlude. There’s a fine line between being sex-positive and self-objectification, and Ariana’s super-seductive video looks a lot like a Calvin Klein ad or a Maxim feature. Why do women’s images of female sexuality so closely resemble male ideals of female sexuality? How can we embody our unique sexual selves apart from media-driven imagery? Lena Dunham has written about stunted sexual fantasy, in which a woman views herself from the outside in—what she looks like, what she’s wearing, not how she feels:

“I never got good at fantasizing again. I got good at performing: back arched, hair flying, assuming attitudes I thought were desirable to a partner who watched either porn or foreign films.”

As for Ariana’s tween and teenage fans, I want them to know that self-actualization takes more than slapping an empowered hashtag on a hot selfie— that looking sexy is not a prerequisite for being strong. Ariana may be a symbol of female agency, but the truth is that young women are struggling in our culture. A new study reveals that adolescent girls’ depression rates are higher than ever, starting as early as age 11. Teen sexual assault statistics remain shocking, with girls age 16-19 at greatest risk of being raped. And when it comes to sexual pleasure, Peggy Orenstein’s research shows that young women consistently put their partners’ enjoyment above their own, a dismal pattern I recognize from my own adolescence. Moving from voicelessness into embodied self-expression has been a lifelong project for me, and it’s only now, in my 40s, that I’m learning to ask for what I want, or simply to reach out and take it.

Lyrics and tweets aren’t enough to create change. I want to see Ariana walk her talk as she continues her megastar reign. But we still need her anthems of female desire, her rebukes to slut-shamers everywhere. Her strong voice counters creepy songs like Pitbull’s “Timber”—a dance jam that reminded me, when I first listened closely, of my dorm-room date rape by a frat-boy when I was 18: “I’m slicker than an oil spill/ She says she won’t, but I bet she will…” With consent teachings like this, who needs rape clubs?

Ariana says she’s going to test her limits, and I hope she relishes doing so. But I want to warn her to be careful. The tricky thing about boundaries is that you often don’t know where they are until they’ve been crossed.

What I hope for my daughters—for young women everywhere— is an authentic experience of sexuality, free from self-consciousness, shame, or violation. May Ariana Grande help lead the way.

Diana Whitney lives in Southern Vermont, where she writes across the genres with a focus on sexuality, parenting, and feminism. Her first book, Wanting It, became an indie bestseller in 2014 and won the Rubery Book Award in poetry. She’s the poetry critic for the San Francisco Chronicle and her essays have appeared in Glamour, The Washington Post, Salon, Ms. Magazine, and many more. When she’s not teaching yoga, she’s finishing a memoir about motherhood and sexuality. Find out more at www.diana-whitney.com

This originally appeared on ROAR. Republished here with permission.

Other Links: