While I’m in favor of encouraging women to feel confident and happy, I worry that today’s body positivity focuses too much on affirming beauty and not enough on deconstructing its necessity.

In the early 2000s, when I was a burgeoning fashionable fat girl, I stumbled across the LiveJournal community Fatshionista. I loved seeing pictures of women my size or larger dressed in stylish, interesting, sexy clothes, embracing bright colors and form-fitting cuts, performing liberation and defiance.

Even while I stayed on the outskirts of body positivity during my high school and college years, I still found a well of confidence and self-esteem that television commercials and women’s magazines never offered me. Today, a Google search for “body positivity” yields nearly 10 million hits, many of them grassroots online communities aiming to challenge prevailing notions of beauty.

The new generation of body revolutionaries, including Internet celebrities like Sonya Renee Taylor and Jes Baker, preach the importance of reclaiming beauty, spreading an intersectional gospel of self-esteem in which you don’t have to be thin, white, able-bodied, or young to be attractive. The message has found its way into pop culture, with singers like Nicki Minaj and Meghan Trainor offering odes to body types beyond what you might find in a Victoria’s Secret catalog.

Even cosmetics companies are getting in on the act. Last year, an ad from the Dove Real Beauty campaign took social media by storm. The viral video showed a police sketch artist who drew two pictures each for a group of women—one sketch based on the woman’s description of herself, the other based on a stranger’s description of her. In its final scene, the women were shown the two sketches side by side; they marveled at how much more beautiful they looked to a stranger than to themselves.

The ad’s statement was ostensibly heartwarming, but it didn’t sit right with me. Everyone in it was thin and able-bodied, and almost everyone was white—hardly a dramatic reversal of conventional beauty standards. And the viral advertisement reminded women that being found beautiful by other people was more important than what they thought of themselves. At the end of the clip, one of the women reflected after seeing the portraits and said, “I should be more grateful of my natural beauty. It impacts everything. It couldn’t be more critical to our happiness.”

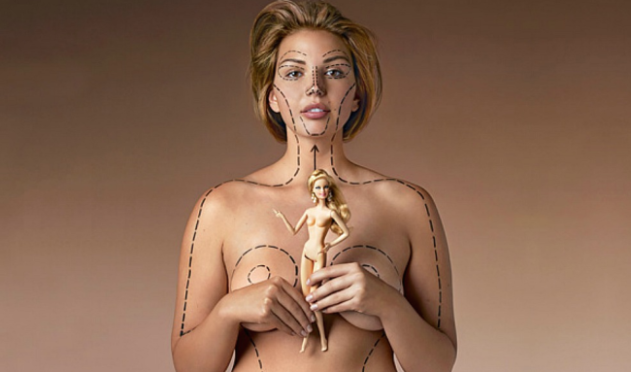

While I’m in favor of encouraging women to feel confident and happy, I worry that today’s body positivity focuses too much on affirming beauty and not enough on deconstructing its necessity. Spreading a message that everyone is beautiful reinforces the underlying assumption that beauty matters.

Recently, a friend of mine—a fat, queer, thoroughly empowered babe—posted on Facebook: “I’m not pretty and I’m fine with that.” Immediately and predictably, the comments were flooded with well-meaning friends saying, “Don’t be ridiculous, you’re beautiful.” Reading the thread made me deeply uncomfortable, even defensive. Here was a woman moving away from an oppressive and harmful hierarchy, and with the best of intentions, her friends were trying to drag her back in.

I’m troubled with using “beauty” as a synonym for feeling valuable and powerful and magnificent. It’s not far removed from nominally inspiring, but ultimately shallow, slogans like “Confidence is sexy” and “Nothing is more attractive than happiness” that treat emotional well-being as an accessory. I seek happiness because it feels good, not because it makes my hair shinier. Happiness, confidence, self-esteem—these things should be ends, not means.

Today’s body positivity has gotten stuck trying to “fix” beauty from the inside rather than moving beyond it. Between the “real women have curves” memes and the furor over un-photoshopped cover girls, we’re fighting to push the margins of beauty an inch in any direction, while reifying the concept itself—struggling to revise the standard but never presuming to overthrow it entirely.

In her essay “The Beauty Bridge,” Jia Tolentino, an editor at Jezebel and the Hairpin, says that such surface-level concepts of empowerment “push women around each other on the narrow, precarious beauty bridge rather than suggesting we just howl like animals and jump right off.”

This is what’s dangerous about making physical attractiveness synonymous with empowerment. The need for visibility often becomes entangled with the “need” for beauty, because media so seldom represents bodies and faces not considered beautiful that it becomes difficult to recognize ourselves if we are outside of the mainstream beauty standard.

But as Tolentino points out, “The desire to be represented by the media as a part of society can (and probably should) be separated from the desire to have all these historically prejudiced institutions recognize you as ‘conventionally’ beautiful.”

Writer and organizer Mia Mingus, in her keynote speech for the 2011 Femmes of Color Symposium said, “Beauty has always been hurled as a weapon. It has always taken the form of an exclusive club, and supposed protection against violence, isolation, and pain, but this is a myth. It is not true, even for those accepted into the club. I don’t think we can reclaim beauty.”

Beauty has always been defined by its opposite. There is no way to excise the concept of ugliness from the concept of beauty, or to permanently keep it from being used against us. The prevailing cultural definition of beauty is rooted in hierarchy, racism, misogyny, ableism, homophobia, ageism, cissexism, and other forms of marginalization. Instead of fighting for a seat at a table so rife with oppression and violence, wouldn’t it be better to find somewhere else to sit?

Not everyone sees beauty as a lost cause. Indeed, reclaiming beauty is central to many activists’ goals. Sonya Renee Taylor, founder of the radically body-positive online community The Body Is Not an Apology, says she strives to “take beauty out of the box.” She sees beauty as the natural inheritance of every person and argues against imposing limits upon it.

“Beauty exists; standards do not,” says Taylor. “Beauty is undefinable, is subjective, is intrinsic to humanity.”

Writer and performer Denise Jolly is a friend of Taylor’s who took on beauty in a 30-day self-portrait project called “Be Beautiful,” which quickly went viral. Jolly photographed her 311-pound body every day wearing nearly nothing, in an attempt to see herself—and love herself—exactly as she is. She explains, “I thought about calling the project something else—Be Brave, Be Brilliant—but all of those are things I am often, and things that people see in me. I am not historically seen as beautiful, and that was the thing that was actually missing.”

The Body Positive is a nonprofit organization that works directly with individuals and communities to support positive body attitudes. Its cofounder and executive director, Connie Sobczak, says that “beauty is an amazing thing if we can reclaim it,” and rejects the idea that the definition of beauty must exclude anyone. “If I say that I can see my own beauty, it doesn’t take away from anyone else’s. It just means I’m a whole human being and I can see my own value, and because of that I can see so much beauty in everything in the world.”

There’s no doubt that the above goals are laudable and that such work does real good. I would certainly rather live in a world where everyone feels worthy and desirable exactly as they are than a world plagued with eating disorders, body dysmorphia, and depression. When society places so much importance on physical beauty and desirability, it’s indisputably better to feel beautiful than not.

And of course, claiming beauty in a culture that has historically denied it can be genuinely empowering. For fat people, people of color, gender-nonconforming people, people with disabilities, and other marginalized communities and individuals, access to being viewed as “beautiful” has long been restricted, and with it the visibility and social capital it can bring. “It’s about taking down those boundaries that assess what beauty is,” says Taylor, “and also about challenging the paradigm that there are certain people who should not be seen, who should not exist in the public sphere.”

In a world where we’re so often told that to be ugly is to be invisible and irrelevant, reclaiming beauty can be a way of refusing to disappear. A powerful example of this is the “Black Is Beautiful” movement that began in the 1960s as a way to counter the prevailing belief that only light skin, straight hair, and white features are desirable.

“The semantics of beauty are so entrenched in our culture that we would have to interrupt it from birth to escape it,” says Jolly. “I don’t think we can sever the word from the language, because getting rid of it leaves no way to affirm people who are already invisible or unseen.” Many of the people arguing for a redefinition of beauty don’t see the concept in aesthetic terms at all. “We can call it what we want,” says Taylor. “For me, that word is ‘beauty,’ but for others it might be something else. It just means that I recognize my inherent value without qualification, that I recognize my power and magnificence.”

If we insist on the primacy of beauty, doesn’t that give the word “ugly” even more power to cause us harm? For years now, fat-positive activists have insisted that the word “fat” is morally neutral; that if you don’t need to be thin to be considered a worthwhile or complete person, then “fat” isn’t an insult, just a descriptor. Similarly, the answer to an oppressive and arbitrary beauty standard should not be to insist that everyone is beautiful, any more than the cure to weight stigma is to declare that everyone is thin. It is to resist and counter the notion that thin and beautiful are the only acceptable things to be.

Instead of insisting that beauty is necessary for everyone, more body-positive activists are working toward making beauty optional—something we can pursue if it matters to us, but also something we can have full and satisfying lives without. We should affirm our bodies for what they can do, how they can feel, the tribulations they’ve survived, and the amazing minds they carry around, without having to first justify their existence by looking pretty.

While I stand with and support anyone who finds power, visibility, or joy in reclaiming the word and the concept of beauty, it shouldn’t be compulsory. There should be space in body positivity for women like me, for anyone who wants access to confidence, happiness, and self-worth without having to use beauty as the vehicle to get there.

Lindsay King-Miller is a queer writer who lives in Denver with her partner, an ever-growing collection of books, and a very spoiled cat. Her first book will be published by Plume in early 2016.

This originally appeared in Bitch Magazine, issue #65. Republished here with permission.

Related Links: