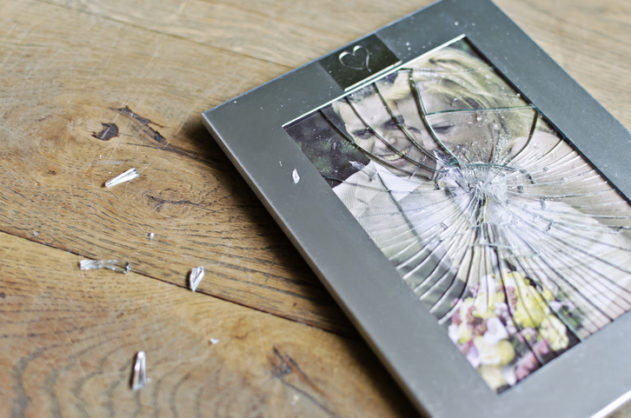

Infidelity is corrosive not only in how it eats away at any future but how it also eats up the past.

…And after

the first minute, when I say, Is this about

her, and he says, No, it’s about

you, we do not speak of her.

— “Unspeakable,” Sharon Olds

How do you get over infidelity? You don’t.

At least, not quickly, and not without the agonies of self-excoriation. Years after the fact, I still wrestle (narcissistically) with these basic questions: “Why wasn’t I enough?” and “How could I not have known for all those years?” I trusted my marriage contract, that vow to faithfulness: “Do you? I do. And do you? I do.” Even when an open marriage was twice suggested (and I said “No” and “Are you kidding me?”), I attributed that solely to my defunct libido, demolished by psych meds and the exhaustion of motherhood, and to his mid-life fantasy of an abstract other woman, rather than an actual other woman he was seeing on the sly.

In the early months of the first year of our 20-year relationship, I was seized with doubt and jealousy: He flew to California to visit, in part, an ex-girlfriend. I yelled at him over the phone, “I don’t believe you! How could you do this to me?”

She was beautiful and willowy and blonde—at least that’s what she looked like in the photographs I scrutinized when he left the apartment to teach or go to the grocery store. In comparison, I was a fumbling, needy giantess, a tangle of jealous insecurities.

“I’m friends with all my exes,” he said. “Get over it or we’re over.” And then he said, with what felt like munificent compassion, “I would never cheat on you. My father did that and I know how damaging it is.”

In “Great Betrayals,” from the New York Times, psychiatrist Anna Fells writes, “Frequently, a year or even less after the discovery of a longstanding lie, the victims are counseled to move on…But it’s not so easy to move on when there’s no solid narrative ground to stand on. Perhaps this is why many patients conclude in their therapy that it’s not the actions or betrayal that they most resent, it’s the lies.”

Lies, yes. I found out about the affair through her ex-husband, who wanted to tell me about my then-husband’s and his wife’s affair years earlier, but my then-husband and his then-wife convinced him that if he told me the truth, I would kill myself. Self-serving justification, but perhaps some truth to this. I’m Bipolar, and at the time, was acutely unstable, which is to say, suicidal and in and out of the hospital. Perhaps they didn’t want to be responsible for my suicide? Perhaps they didn’t want to be responsible for their lies?

For months, after finding out about their affair, I was mired in grief. My son worried about me, about my crying jags in the bathroom, so he asked his father why I was so sad. What did he say to my son? That my sadness was due to my mental illness, rather than, say, to my divorce, which was not yet then a year old, or to my discovery of his affair with a mutual friend, someone who used to unfurl her towel next to mine on the beach and tag along on family adventures. Easier to point to my Bipolar disorder as the reason for difficult, unshakeable emotion.

That attribution is a reflex, even for me—checking and rechecking in with myself and trusted friends about the legitimacy of what and how much I should feel. Remember: I believed him when he said my jealousy was unfounded all those years earlier and carried that shame for any of my volcanic eruptions. “Am I overreacting?” I’d ask him.

“Yes,” he’d invariably say. “You need to check yourself.”

Certainly, before stability, before the balancing effects of lithium, my moods flipped between free-wheeling suicidal despair, anger, and mania. Now, years into recovery, I still ask trusted friends, “Is it OK to be depressed over the divorce even two years later? Is it OK to be angry that the other woman sits on the sidelines at my kids’ games and eats off the china my grandmother gave us for our wedding? Is it OK that I’m not OK with any of this except maybe being on my own?”

I am not OK with any of this, not really. I still remember the man who called me his muse, who wrote me poetry on paper towels, who wooed me after our first sleepover with a spinach and feta omelet.

It’s easier, with ladylike restraint, to write (and read) about how grief hollows me out. Some days (especially sleepless nights), I feel pummeled to the floor, knocked out. It’s easier to write (and read) about my loneliness of being on my own, without a partner, without filial love. Easier to write (and read) about my guilt over my years of illness that he said was the cause of marital collapse. “I’m sorry,” he said when we first talked of divorce, “but your illness changed the way I saw you.”

We were sitting on the front porch, a late July afternoon, and the kids were playing somewhere else, oblivious to the fact that we were talking about ending our family. “Let’s be honest,” he said. “Let’s be kind to each other,” he said.

“Yes,” I said. “Because we still love each other.”

His words felt right and true when he said them because I agreed not loving me could be the only rational consequence of my illness. Could I really expect his continued love after he hid knives and medications from me? After he followed me to the toilet after meals, making sure I didn’t purge? After he visited me in the psych ward over and over, eventually believing, as most, that recovery was impossible? Similarly, who would fault his infidelity with a crazy wife like me?

“People said I should leave you,” he said. Again, I wasn’t angry but grateful since shame annihilates self-worth. In retrospect, I wonder if this same counsel would be offered for an unremitting physical illness—cancer, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s? Mental disorders are often misrepresented as acts of (ill)will: You can choose to think better, act better, feel better, but you don’t.

Grief. Loneliness. Guilt.

But what about anger? Anger is dangerous and disruptive. Angry women are irrational bitches (“Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.”). Women worth loving keep quiet, ride out the storm, placidly smile even though the boat is sinking. Friends don’t really want to hear about my anger, though other women I know who have been cheated on? The anger we all share simmers and sometimes rages, and it is not over being cast off for another woman, but over the lies and deceit.

The last time I was an inpatient, I was on the hospital pay phone, listening to my husband tell me that this was my last chance to be truthful with my treatment team, that our marriage depended on this. At the same time he was demanding my honesty, he was with the other woman who had come on a clandestine visit while I was in the hospital. “You lied first with your drinking and eating disorder,” he said. A screwy logic but one that comes back to the acceptable, mutually agreed upon source: The affair was because of my illness, and thus, his lies were my responsibility.

Most of my anger, though, concerns revision. Though my memory’s hard drive was wiped out by electric shock treatments, a few scenes surface and repeat, ones that I’ve held onto as evidence that married love survived those years of pain: Our shared rhythm at the end of the day, managing kids and meals and dogs and cats; lying next to each other on the beach in Greece or Jamaica; sprawling on the couch watching movies, eating pizza, relieved that our life was again reliable. And of course, his assurances of love and fidelity and our shared future, which in painful retrospect, were perhaps true for some years, but then were easy lies meant for cover for the secret phone calls, emails, and meetings.

How do I understand what was true about my marriage? About his love for me and mine for him? Infidelity is corrosive not only in how it eats away at any future but how it also eats up the past. Just last week, one of those Facebook Memories popped up, a posting from 2012: “Home after a few great days in Jamaica with my husband—my Christmas present in March. Read 5 novels in 5 days, bonded with our Canadian twins, snorkeled, jet-skied, lazed on the beach, drank a lot of Blue Mountain coffee. Sad to leave the sun and sand and Jah-love behind, but great to be home with abundant kid-love again!”

When I found out about their affair, I went through phone records. Six hundred secret phone calls in just one year, two and three times a day. But in March 2012, almost an entire week of their silence, the week my husband and I were in Jamaica, the week I thought was about the restoration of our marriage. After all, we made love in the morning and at night and even in the afternoons. But looking at the phone records? He called her from the airport before take-off, and almost immediately upon landing. So, my version of our time together is, in retrospect, false: He was not with me, but still and already with her, and I just didn’t know it. How do I trust any of our life together now?

What holds true is this repeated scene, exposed now, and still capable of leaving me breathless: At night, after we watched movies, said goodnight, (“Love you, Love you”—the short cuts of reassurance and recommitment), and I went upstairs to bed, he called her, and they talked of love and desire and their future together.

Living in truth is always the hardest choice. How much kinder we might be with each other if only he’d come to me all those years ago when he was first falling in love with her and out of love with me, and simply said, “I don’t want to lie to you or cheat on you, but I might if I don’t tell you my truth.” Anger, sure, at first, but likely softening into forgiveness. After all, he’d forgiven much of me over the years as I was not always a truthful and loving wife in my illness. And really, who can claim another’s heart for keeps?

In the end, perhaps the only way to get over his infidelity is to trust in my life again, in the integrity of my days and nights, in the knowledge that the only person for whom I am enough, and to whom I owe the fidelity of my heart, and of whom I demand the truth is myself.

Kerry Neville is the author of the short story collection, Necessary Lies, and of the forthcoming collection, Remember to Forget Me. Her essays and fiction appear have appeared in journals and online magazines.

Other Links: