Queer parents and anyone who uses non-traditional methods to build families, whether that means sperm or egg donation, IVF, surrogacy, or adoption, complicate the question of what it means to be a parent, what it means to be a family, what it means to be a mother.

I have never wanted to give birth. I keep waiting for the desire to reveal itself, for time or circumstance to wind the biological clock that has so far been silent, but nothing has happened yet. I want to be a parent, to love and raise and care for my child as best I possibly can, but there is nothing in me that yearns to be the one to bring that child into the world.

My partner Charlie is a different story. Although he’s genderqueer and goes by male pronouns, pregnancy and birth are a few of the aspects of traditionally feminine experience that appeal to him—actually, “fascinate” might be the better word. Charlie has been stockpiling books on pregnancy and birth for years and has basically been writing his birth plan since becoming literate. When we started talking about having a baby together, there was never any question regarding who would carry the child.

Some two-uterus couples choose reciprocal IVF, or using one partner’s egg and the other partner’s uterus, so that both have a physical connection to the child, but that struck us an unnecessarily complicated. “You don’t have to share genes to be a parent,” we figured, and went ahead with trying to get Charlie knocked up as close to the old-fashioned way as possible. I’ve never been sad that I won’t be biologically related to our baby, and indeed, watching Charlie battle intense morning sickness for the past two months has made me more certain than ever that non-gestational parenthood is the best gig in town.

But, although I’ve always been an active participant in Charlie’s attempts to conceive, going through the process of assisted reproduction (first intrauterine insemination, then, when that didn’t work, IVF) made me feel like little more than a bystander. Reproductive endocrinology clinics don’t have a lot of use for anyone who isn’t contributing genetic material to try to make a baby. Charlie’s doctors seldom talked to me, included me in decision-making, or indeed even acknowledged that I was in the room. They didn’t seem to see us as a couple trying to build our family; they only saw Charlie, and then only as a condition—first infertility, now pregnancy—that requires tending to.

Getting pregnant with medical assistance was frustrating and alienating for Charlie, who was poked, prodded, speculumed, injected, X-rayed, and ultrasounded to within an inch of his life, but being on the sidelines was alienating in an entirely different way for me. The process of trying to conceive our child made me realize that there will always be people who see me as less of a parent than Charlie, which in turn made me realize that I’ll need to create a definition of parenthood that works for me—and try my best not to care what other people think about it.

Even the casual language of friends and loved ones occasionally trips me up with its unconsidered assumptions. Everyone from family members to doctors has asked us about the baby’s “father,” by which they mean the sperm donor. If biology defines familial roles then Charlie is the mother, some dude in California we’ve never met is the father, and I’m just the weird roommate.

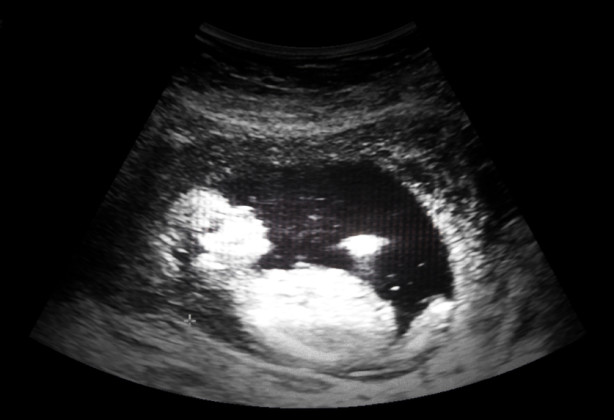

But I knew the child Charlie is carrying before he or she was even conceived. I was there when the egg that would become our baby was extracted, and the day it was transferred back into Charlie’s uterus as a five-day-old blastocyst. I’ve painted a nursery, read parenting books, and compared stroller models. Even though my body wasn’t involved in creating our child, he or she would not exist without me. Biology be damned; this is our baby. I’ve heard its heartbeat and seen it develop on ultrasound pictures from a tiny blob of cells to something that resembles a human being. I sing it lullabies and I’ll probably catch it when it’s born. I am this child’s mother.

Queer parents and anyone who uses non-traditional methods to build families, whether that means sperm or egg donation, IVF, surrogacy, or adoption, complicate the question of what it means to be a parent, what it means to be a family, what it means to be a mother. Parenthood isn’t nearly as simple as I learned in fourth-grade sex ed. There is so much more to it than introducing egg to sperm. I love this little life more than I would have guessed I could love someone I’ve never even met.

I used to think it was totally goofy when men said “we’re pregnant” to describe their female partners carrying a child, and while I still understand the eye-roll that people who have actually given birth award that phrase—like, yeah, we don’t have morning sickness and indigestion and have to buy a whole new temporary wardrobe, champ—there’s a part of me that wants to say it too, to define myself as someone with a stake in this process. Charlie is pregnant, but we’re both expecting a baby. We’re both preparing for this new person to enter our lives. We will both be transformed by the experience.

Sure, sometimes it makes me a little sad to realize that my child won’t have my eyes or my smile (although he or she will be lucky not to inherit my family’s giant teeth and the orthodontic bills that come with them), but the things I really want to hand down are the ones I can teach—patience, compassion, integrity, love of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Parenthood is not just biological—it’s formed from love and time and patience and care and being willing to sacrifice anything for your child. My parents are my parents not because they contributed to my genetic makeup, but because they brushed my hair and read me books and attended my spelling bees and tolerated my teen angst. Those are the things I’ll provide for my child, things that mean more than biology.

Just over a week ago, I was wished a happy Mother’s Day by several friends and family members who know that we’re expecting a baby. I pushed their well-wishes away, thinking I’m not a mother, not yet. I remembered the consent form Charlie and I signed before the IVF procedure: Charlie signed in the blank for “mother,” I in the space for “father or domestic partner.” While the gesture to inclusion for same-sex couples is nice, it underlines the message I’ve received so often: Pregnancy is what makes you a mother. If you’re not giving birth, you don’t count.

But I do count. I am my child’s mother. And next year when Mother’s Day rolls around, someone had better make me some damn pancakes.

Lindsay King-Miller is a queer writer who lives in Denver with her partner, an ever-growing collection of books, and a very spoiled cat. Her first book will be published by Plume in early 2016.

Related Links: